History

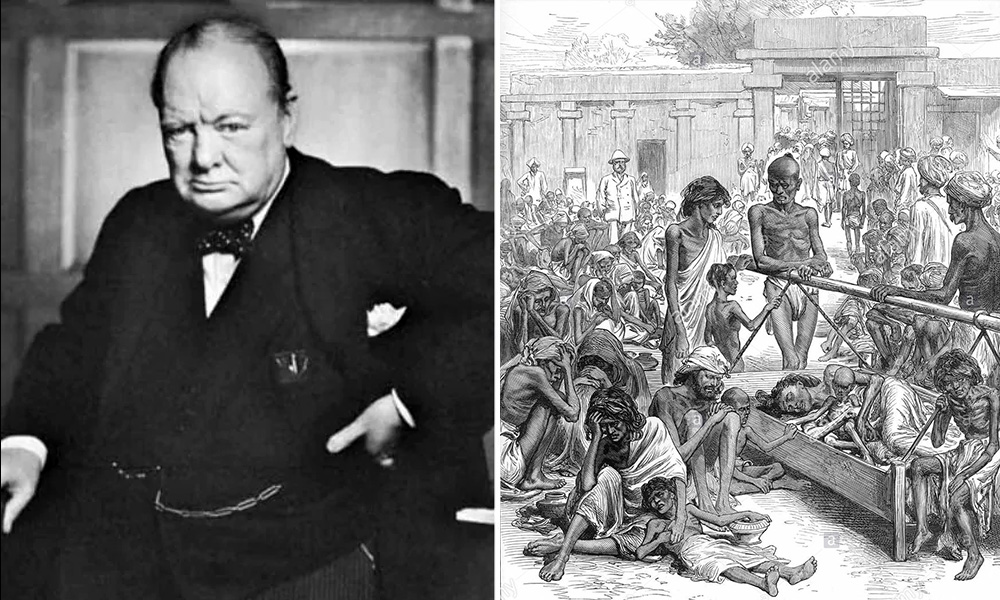

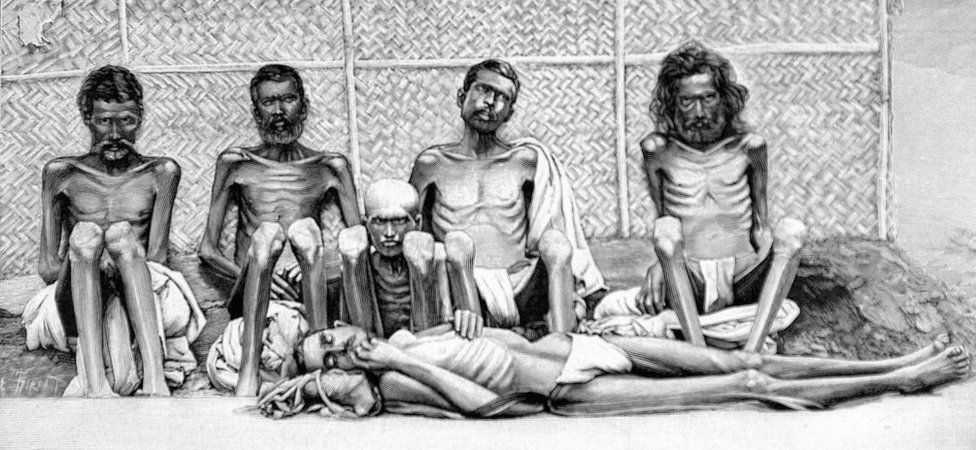

British Induced Indian Holocaust Resulted in Millions of deaths

Published

5 years agoon

By

Vedic Tribe

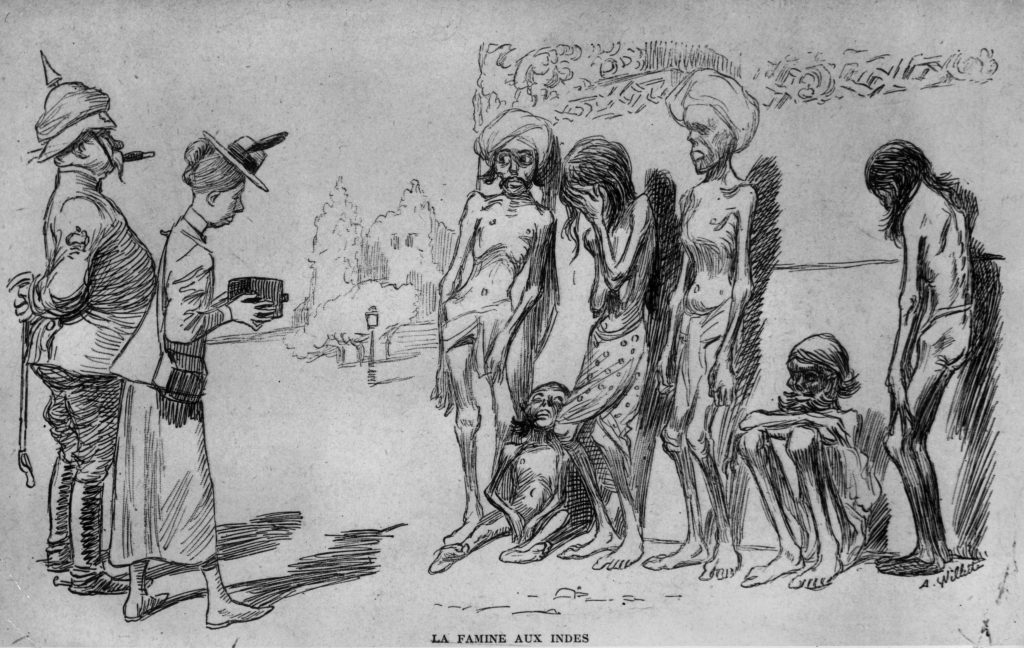

During the terrible famine of 1838, according to one reporter, millions of pounds of rice and other edible grains were exported from Calcutta, to feed the kidnapped Indian Coolies, who had been sent to the Mauritius, to work in the fields. Food was exported by India’s British administration to Allied soldiers fighting in World War Two and denied to the local population. These are just the figures of the British-man-made famines, it does not include the Epidemics induced by Famines, Anglo-Indian Wars, Indians killed fighting for the British, Freedom Fighters martyred by the British. If all these are included the figures reaches over 1.8 Billion mark.

The current outbreak of food shortages and famine internationally should come as no surprise to anyone who knows the history of British imperial free-trade policy. To buttress that point, we present here indictments of that policy by two leading statesmen with personal knowledge—Abraham Lincoln’s economic advisor Henry Carey, and the founder of modern China, Sun Yat-sen—in addition to this overview article, written in 1991, from the archives of the LaRouche movement.

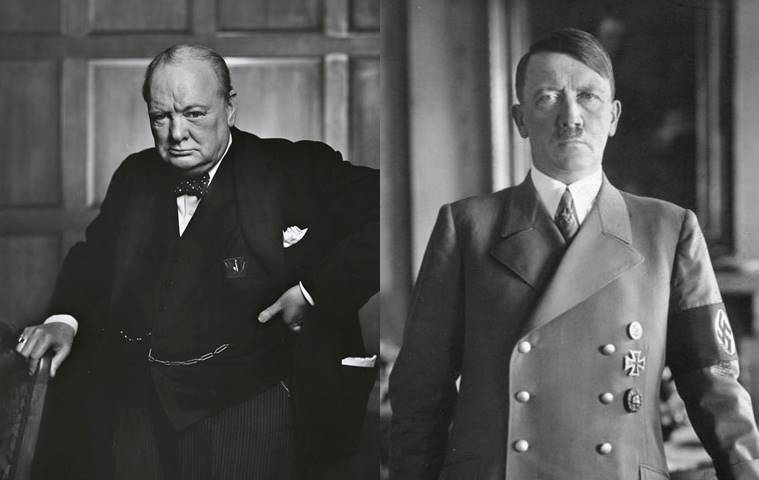

Before Hitler, there was Britain, and the British famine policy in India.

As many look with horror at the starvation now being induced in Africa by agencies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), and the grain cartels, few know that in a previous century the British pioneered all these techniques in India. What follows is a brief outline of the British famine policy in India from 1764 to 1914, and how the British developed the deliberate use of famine and food control as the principal means of rule.

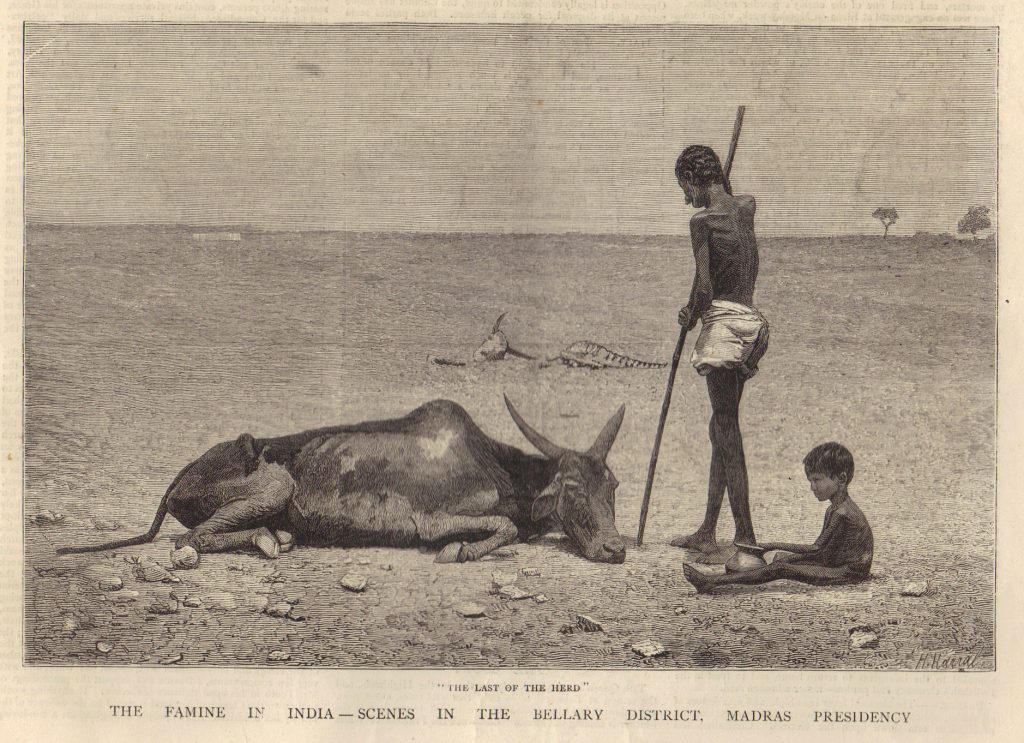

To understand the question of famine in India, one must first start with the fact that India’s climate is characterized by the monsoon, in which a region’s weather follows the pattern of a dry climate for most of the year; then comes a period of rains, which is the monsoon. At least once in the course of a decade, the monsoon fails to arrive in any given region.

Traditional agriculture in India and other countries always planned for this by laying aside foodstocks at the village level, which ensured that there would be adequate food in drought years. The central administrative authority, whether it was a Hindu prince, or the Moghul court, would suspend taxes for that period of economic insecurity. Prior to British rule, it was understood that famine needed to be avoided if the central authority was to have any legitimacy as the ruler of an area. The British changed all this.

As B.M. Bhatia writes in his 1967 book, Famines in India: “From about the beginning of the eleventh century to the end of the eighteenth there were 14 major famines in India.” This is roughly two per century. Under the period of East India Company rule from 1765-1858 there occurred 16 major famines, a rate eight times higher than what had been common before. Then, under the period of British Colonial Office rule from 1859 to 1914, there was a major famine in India an average of every two years, or 25 times the historical rate before British rule! The rest of the world’s population was growing due to technological progress, but the population of India remained at approximately 220 million for over a century prior to 1914.

Deliberately inducing a major famine more or less every two years, was, for over half a century, the backbone of British colonial policy in India.

The history of the British in India is a history of the deliberate creation of famines. Such famines resulted from the policies of the East India Company. Those policies included looting through “tax farming,” usury, and outright slavery of the indigenous population.

As we shall see, a limit to this rapine was reached in the middle of the 19th Century, leading to the first struggle for Indian independence, which began with the Sepoy Mutiny. Following that revolt, a new policy was developed by the British Colonial Office, which took over all the operations of the East India Company. The new policy revolved around creating famines in selected regions on a continuous basis, with the goal of creating a mass of starving people who could be used as slave labor, needed by the British to build the infrastructure of British rule.

East India Company Rule

The British East India Company began the administrative takeover of India in 1764-1765. The company was appointed diwan, or governor, over the area of Bengal by the collapsing Moghul Empire. The British entered India as the administrative rulers and tax collectors of the Moghul court.

As tax collectors, the previous supposedly “rapacious” Moghul agents, had collected the marketable equivalent of £818,000 sterling from the area of Bengal. In 1765-66, the first year of East India Company diwanship, the company was able to collect the equivalent of £1,470,000; and by 1790-1791, this figure had risen to £2,680,000. According to Jean Beauchamp’s British Imperialism in India, Warren Hastings, the company’s chief officer in India, wrote the following to the company’s board of directors in London:

“Not withstanding the loss of at least one-third of the inhabitants of the province, and consequent decrease in cultivation, net collections of the year 1771 exceeded those of 1768…. It was naturally to be expected that the diminution of the revenue should have kept an equal place with the other consequences of so great a calamity. That it did not was owing to its being violently kept up to its former standard.”

The great calamity mentioned was perhaps the worst famine in Indian history, which struck the provinces of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. It is estimated that no fewer than 10 million perished from starvation. The severity of this famine was a direct result of East India Company looting.

Tax Farming

What the Company had done to increase the tax revenue was to set up a system of “outsourcing” the right to tax the land. This is what is known as “tax farming.” The tax collector had the right to obtain as much tax as he could get, since he had bought these rights at auction. In turn, the one who was taxed, the registered landholder, called zamindari, was allowed to extract whatever he could for himself and for the tax collector from the poor peasant who worked the land.

The zamindari, who was subject only to the payment of the company’s taxes, essentially had complete power over all the land and all its cultivators.

Through this looting system, the Company left nothing in reserve for the times when the monsoons would fail. In addition, little or no maintenance was allowed for the cultivators’ infrastructure, such as the irrigation works.

The results were horrendous, as more of India’s land area came under Company rule.

The drain of wealth from India based on a tax-farming system, the destruction of native textile industry by the “free market” dumping of British textiles, and the plantation economy of opium, led eventually to a fierce resistance from the communal based population. This finally led to the Sepoy Mutiny of the zamindaris and others, especially those who lived in areas not totally under Company control. It almost broke the British Empire.

In the end, the East India Company was relieved of its rule in India and was replaced by a governor-general, and a colonial administration. The commission which recommended this change concluded that the problem was the lack of a transportation and communications infrastructure, necessary to hold subject such a vast country. Also, the commissioners concluded, there was a need for an Indian ruling class that would function as intermediaries for the British colonialists.1

Slave Labor Policy

Britain’s colonial overseers agreed on the need for the development of a rudimentary infrastructure to increase the efficiency of their rule, and looting of India. But the Empire had a problem. The proposed grid of railroads and large-scale irrigation works was too expensive, from the colonialists’ point of view. So, the decision was made to force the already plundered Indian population to pay for these development projects.

This presented another serious problem. India, at that time, did not have a landless laboring class which could provide a pool of cheap labor for such projects. The caste system of India was all-encompassing. As Bhitia documents, the ritual distribution of goods at the communal level, based on caste and guild relations, made it undesirable for families and individuals to leave this system, especially to become slaves for the British railroad and irrigation projects.

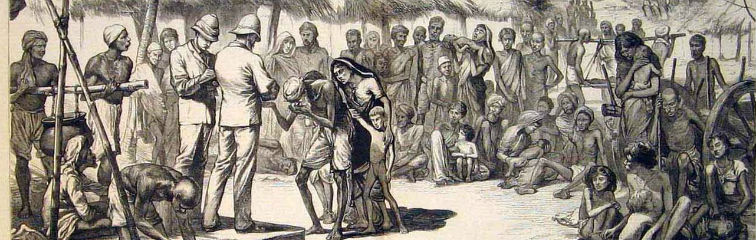

The British solution to this problem was “famine relief.” To build the railroads, the British set up “famine relief works.” A famine would create the condition, such that, faced with certain death from lack of food, an Indian would be forced to “choose” to go to a famine relief center, much like a starving famine victim in Africa would do today. However, once having done this, the individual lost his caste relations and privileges. Then he was told that if he wanted to continue to eat, he must work, building the railroad in exchange for food.

At these projects, less than minimum subsistence was the norm, much like a Nazi forced-labor concentration camp. As yesterday’s famine victims dropped dead from exhaustion and slow starvation on the railroad or irrigation project, today’s famine refugees were making their way into this socalled famine relief system. This system would today be labeled euphemistically, the “recycling” of the work force.

With the advent of railways, it became easier for traders to buy up food and other goods when they were cheap, and in some cases, even when costly, and export them to England — much in the same manner as the British let the Irish starve during the potato famine, rather than allow the wheat, barley, and rye grown in Ireland for England to be used to feed the Irish.

Under these conditions, the nature of famines and scarcities began to change. Whereas in the past, famine had been a regional phenomenon, under this British policy food became scarce throughout the country, hitting the poorest in a devastating manner. It was these famine-stricken poor who then continued to supply the labor for the relief-works.

The Rise of Usury

The development of the railroads also helped to develop a class of Indian money-lenders, who became the intermediaries for the British. This allowed for the British to control even areas which were not affected by crop failures.

Such areas were hit with multiple increases in prices because of the demand placed on their food from other areas of the country. Money-lenders would then sell British goods to Indians at inflated prices, and buy their grain at low prices. Then they would sell that grain at high prices, either on the international market, or back to the same people in times of famine.

Since these transactions were carried out largely on a credit basis, vast segments of the population became debt slaves to the money-lenders, if they were fortunate enough to escape having to work on famine relief projects. In addition, the British played this system of debt-slavery off against the traditional caste and guild system, which had never had to deal with such a monstrosity.

This system brought to the fore a class of money-lenders who became the power through which the British were able to offset, in part, the resistance within India to their rule coming from the communal base.

The spread of famine throughout India can be measured in the expansion of the railroad system. There were 288 miles of rail in India in 1857; 1,599 miles in 1861; and 3,373 miles in 1865. By 1881, there were 9,891 miles; there were 19,555 miles by 1895; and 34,656 miles by 1914.

With the expansion of the railroads, and “famine relief” which built the railroads, the exports of food grains rose rapidly. The export of rice grew from12,697,983 hundred-weight in 1867-68, to 18,428,625 hundred-weight in 1877-78. Wheat exports grew 22-fold during this same period, from 299,385 hundredweight to 6,373,168 hundred-weight. The criminal nature of this policy is clearly seen, since 1876-78 were major famine years. The export of rice reached 30.3 million hundredweight, and wheat reached 30.3 million hundred-weight in 1891-92.

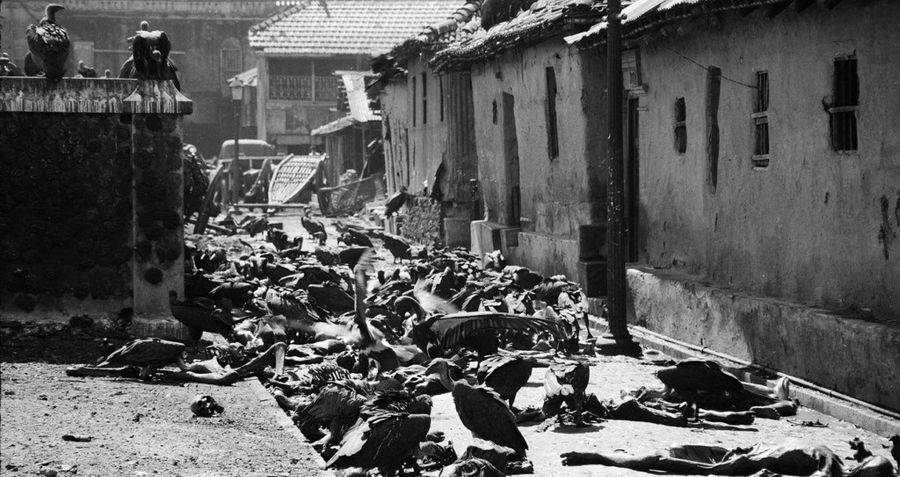

The worst famine was in 1896-97, which affected 62.4 million people. This resulted, among other things, according to Bhatia, in “civil commotion and unrest in Bombay against continuing exports of food grains from the presidency at a time when the people faced the threat of famine. The government of India, however, refused to change its food policy and steadfastly clung to the view so far held that, ‘even in the worst conceivable emergency, so long as trade is free to follow its normal course, we should do far more harm than good by attempting to interfere….’”

Does this sound all too familiar? The [George H.W.] Bush Administration has proclaimed a New World Order based on “free trade” and an end to the “restrictions” imposed by national sovereignty. As food and other basic resources increasingly come under the control of Euro-Anglo-American cartels, most of the world is slated to become much like India was under the British.

Bush’s New World Order is in fact nothing new, and the principal instrument of rule in this new world order is scheduled to be famine, and “famine relief” projects for the victims.

If people don’t wake up, a day will come when you may lose your cherished low-paying job, and find yourself homeless and on the soup line—only you will be told there’s no slop to eat, unless you join a work gang.

Slave labor, famine, and government-protected drug lords, like the British East India Company, are to be your masters in this New World Order. It has been done before!

Now maybe you will think twice when you view the British Broadcasting Corporation’s films of the “glorious days of the British Raj in India” which you see on PBS. British policy in India was nothing less than deliberate genocide. We face the same policy today, this time on a global scale.

China’s Sun Yat-sen on British Imperial Tyranny

In his book The Vital Problem of China, written in 1917, as a polemic against China joining the British (and the United States) in the Great War (World War I) against Germany, modern China’s Founding Father Sun Yat-sen (1866- 1925) writes that Germany stands accused of mistreating Belgium and Luxemburg. But, he notes:

“Every year, England takes large quantities of food stuffs for her own consumption from India, where in the last ten years, 19 million people have died of starvation. It must not be imagined for a moment that India is suffering from underproduction. The fact is that what India has produced for herself has been wrested away by England…. Is that any better than submarine warfare? … Nominally, of course, the British are not plundering, but in fact the exorbitant taxation and tyrannical rule in India are such as to make it impossible for the natives to maintain their livelihood; it is nothing but plunder on a grand scale.”

Sun says that England accuses Germany of asserting that “Might makes right,” but asks: “Is it right for England to rob China of Hong Kong and Burma, to force our people to buy and smoke opium, and to mark out portions of Chinese territory as her sphere of influence? [Sun notes that England has declared as its “sphere of influence” within China, all of Tibet, Sichuan, and the Yangtse Valley—28% of China’s land area.] If one really wants to champion the cause of justice today, one should first declare war on England, France and Russia, not Germany and Austria…. But China does not want to declare any war.”

Sun reports that the British waged war against France in the late 18th Century, “not because England wanted to redress any possible wrongs suffered,” but purely a policy of “rallying the weaker countries to crush the strongest, . . . simply because France in the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV was the strongest country in Europe…. In order to maintain her own interests, England cannot allow any country on the European Continent to grow too strong, and when any other country grows too strong, she must get all other countries to join her in overthrowing that country.”

“When another country is strong enough to be utilized, Britain sacrifices her own allies to satisfy its desires, but when that country becomes too weak to be of any use to herself, she sacrifices it to please other countries.”

Britain’s relation to its friends, wrote Sun, is like a farmer to a silkworm: “After all the silk had been drawn from the cocoons, they are destroyed by fire, or used as fish food.”

With this sense of the evil imperial character of the British, Sun forecast, correctly, that, were China to join the war on the side of the Allies, then “whether the Allies will win or not, China will be Britain’s victim.” In fact, at the Versailles Conference after World War I, Britain divided up China as spoils for those nations which had joined them in the war on Germany. He added: “It is lamentable that the would-be victims should be so willing to place themselves at the disposal of Britain and allow themselves to be tortured and mangled.”—Michael Billington

History

Snakes and Ladders, Originated in Ancient India called Mokshapat or Moksha Patamu

Published

5 years agoon

January 21, 2021By

Vedic Tribe

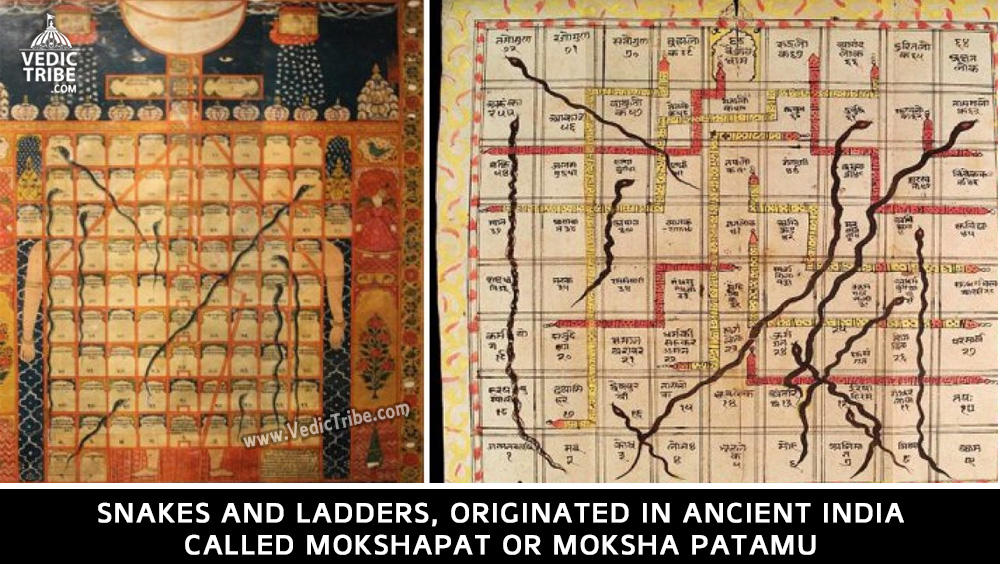

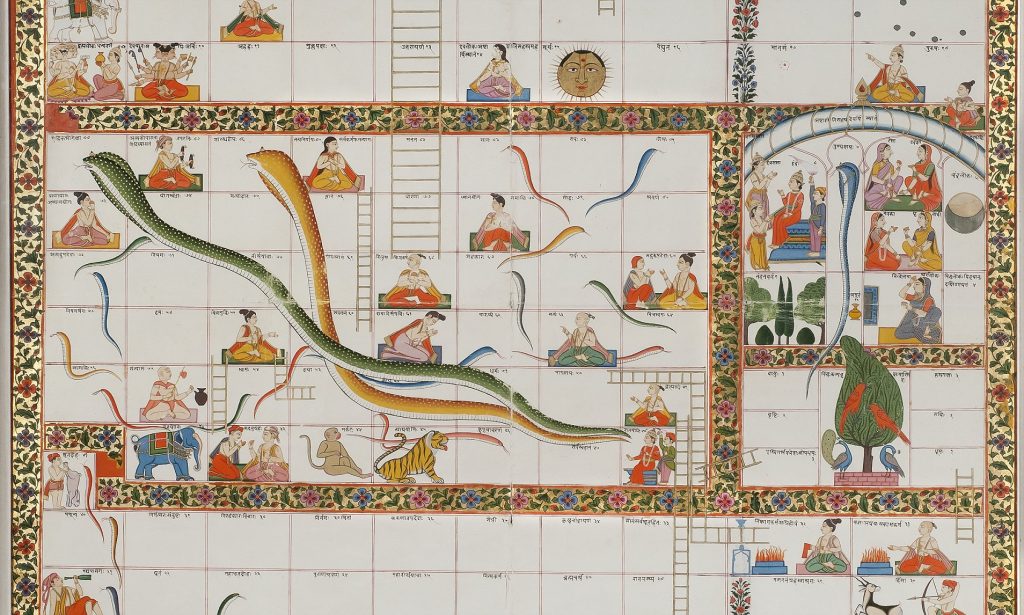

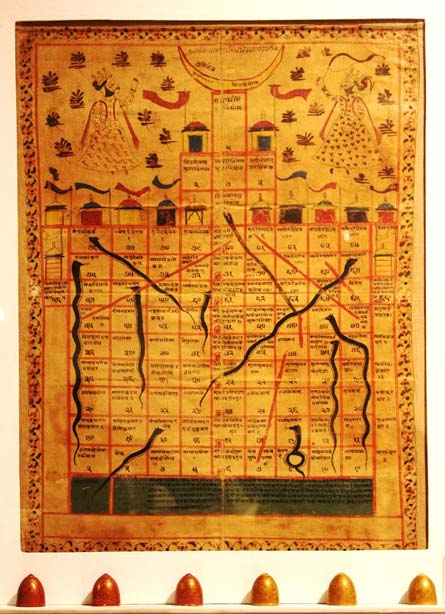

The board game, today called Snakes and Ladders, originated in ancient India, where it was known with the name Mokshapat or Moksha Patamu.

It’s not exactly known when or who invented it, though it’s believed the game was played at a time as early as 2nd century BC. According to some historians, the game was invented by Saint Gyandev.

Originally, the game was used as a part of moral instruction to children. The squares in which ladders start were each supposed to stand for a virtue, and those housing the head of a snake were supposed to stand for an evil. The snakes outnumbered the ladders in the original Hindu game. The game was transported to England by the colonial rulers in the latter part of the 19th century, with some modifications.

Through its several modifications over the decades, however, the meaning of the game has remained the same — ‘that good deeds will take people to heaven (Moksha) while evil deeds will lead to a cycle of rebirths in lower form of life (Patamu).

The modified game was named Snakes and Ladders and stripped of its moral and religious aspects and the number of ladders and snakes were equalized. In 1943, the game was introduced in the US under the name Chutes and Ladders.

The Game of Knowledge

Originally, the game of Snakes and Ladders was known variously as Gyan Chaupar (meaning ‘Game of Knowledge), Mokshapat, and Moksha Patamu, and was originally a Hindu game. Nobody knows for sure as to who invented this game, or when it was created.

It may be said that whilst the gameplay of Gyan Chaupar is the same as today’s Snakes and Ladders, the board and higher objective of the game may be said to be quite different. Like the modern Snakes and Ladders board, the number of squares in that of Gyan Chaupar may vary. One version of this board, for instance, contains 72 squares, whilst another has 100. A major difference between the traditional and modern versions is the fact that in the former, a virtue or a vice and the effects of these virtues and vices, or something neutral is placed within each box.

For instance, in an Indian Gyan Chaupar board of 72 boxes, squares number 24, 44, and 55 have the vices of bad company, false knowledge, and ego respectively. As the game places great emphasis on karma, the Hindu principle of cause and effect, each vice (the snakes’ heads) has a corresponding effect. Thus, for the vices mentioned above, the corresponding effects are conceit or vanity, plane of sensuality, and illusion. On the other hand, the virtues of purification, true faith, and conscience are contained in squares number 10, 28, and 46, and these lead to heavenly plane, plane of truth, and happiness respectively. In this version of the board, the goal is to reach box number 68, which is the plane of Shiva.

Religious Teaching Tool

This game was so popular that it was also adopted and adapted by other religions that existed in the Indian subcontinent. It is known that Jain, Buddhist, and Muslim adaptations of the game exist, as the concepts of cause and effect, and reward and punishment, are common to them. For devout followers of these religions, the game may be played as a form of meditation, as a communal exercise, and even as part of one’s religious studies without the use of more conventional books or sermons.

It may be added that many of the surviving game boards are works of art in their own right, as they contain elaborate illustrations of human figures, architecture, flora and fauna, etc. These boards were commonly made of painted cloth, and most of the extant ones date from after the middle of the18th century AD.

The Modern Game

The game of Gyan Chaupar became Snakes and Ladders towards the end of the 19 th century, when it was introduced to Great Britain by India’s colonial rulers. Whilst the original gameplay was maintained, its underlying philosophical message was greatly diminished. The religious virtues and vices were replaced by two-part cartoon dramas connected either by a snake or a ladder. Additionally, the number of snakes and ladders were equalized, whilst in the original ones, there were usually more snakes than ladders, which symbolizes the belief that it is far easier to fall prey to vice than to uphold virtue. From Great Britain, the game traveled to the United States, where it was introduced in 1943 by Milton Bradley as Chutes and Ladders.

Bharat

Telhara University – Older than Nalanda, Vikramshila Universities

Published

5 years agoon

December 29, 2020By

Vedic Tribe

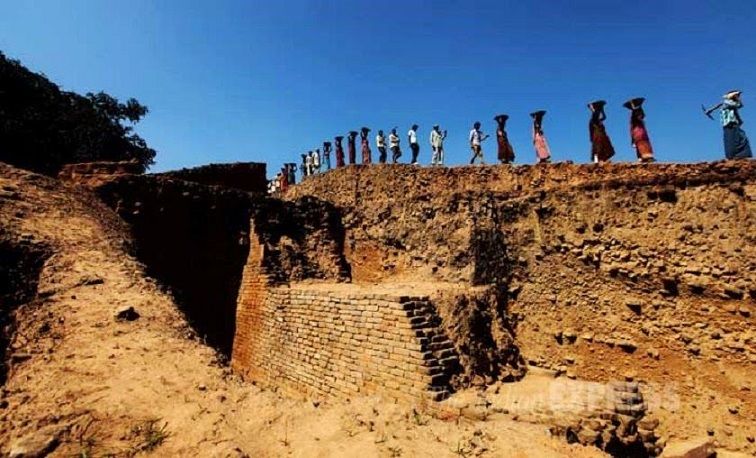

It was a useful mound, no doubt. A good vantage point where villagers occasionally relieved themselves.

But who would have thought that deep beneath its golden brown earth would be stories of dynasties and empires that now suggest that this — Telhara, a village 33 km from the ruins of the more famous Nalanda University — could be ‘Tilas-akiya’ or ‘Tiladhak’, the place Chinese traveler Hiuen Tsang visited and wrote about during his travels through India in 7th century AD? So far, there were only vague references but recent excavations at the mound suggest that Telhara was indeed an ancient university or seat of learning with seven monasteries.

The Bihar government has been calling the Telhara project one of its biggest after the excavations that unearthed Nalanda and Vikramshila universities. The excavation at Telhara should have happened earlier, say experts, but the site lost out to the more famous Nalanda.

The Telhara project that started on December 26, 2009, has so far come across over 1,000 priceless finds from 30-odd trenches — seals and sealing, red sandstone, black stone or blue basalt statues of Buddha and several Hindu deities, miniature bronze and terracotta stupas and statues and figurines that go back to the Gupta (320-550 AD) and Pala (750-1174 AD) empires. But the 2.6-acre mound has now thrown up the most tantalising find yet — evidence of a three-storied structure, prayer hall and a platform to seat over 1,000 monks or students of Mahayana Buddhism.

The terracotta monastery seals — a chakra flanked by two deers — unearthed at Telhara are similar to those at Nalanda, suggesting Telhara or Tiladhak was another great seat of learning besides Nalanda and Odantpuri during the Gupta and Pala reigns. It was the discovery of a similar monastery seal that clinched it for Nalanda University.

Former Archaeological Survey of India director B S Verma, who between 1971 and ’81 supervised the excavation at the site of the ancient Vikramshila university, says, “Telhara or Tiladhak has much more convincing epigraphical proofs — monastery inscriptions — than Vikramshila. The findings that match Hiuen Tsang’s account do more to convince that the place was a university or mahavihara similar to Nalanda.”

In his book, The Antiquarian Remains in Bihar, historian D R Patil writes about Hiuen Tsang’s description of Telhara. “Hiuen Tsang describes Telhara or Tilas-akiya as containing a number of monasteries or viharas, about seven in number, accommodating about 1,000 monks studying in Mahayan. These buildings, he says, had courtyards, three-storied pavilions, towers, gates and were crowned by cupolas with hanging bells. The doors and windows, pillars and beams have bas relieves (sculptures in guilded copper). In the middle vihara is a statue of Tara Bodhisatva and to the right (is) one of Avlokiteshwar”.

Other history books too talk of Tiladhak monastery, on the western side of Nalanda, as having four big halls and three staircases. It is said the mahavihara or university was built by one of the descendants of Magadha ruler Bimbisara. The monastery was decorated with copper and also had small copper bells that gently chimed in the breeze.

For months now, the excavation has been unearthing these stories. Apart from the mound that is now being dug up, Telhara has six other mounds — five of which have settlements and one which is partially elevated.

Atul Kumar Verma, director (archaeology) of the Bihar government’s Department of Art and Culture, says, “Since the excavations suggest that Telhara might have been a contemporary of Nalanda, it is quite possible that it was either an independent university for specialized education or that students graduating from Nalanda University would come here for specialized study. It is a great feeling to see the place emerging as the next big find after Nalanda. It has also aroused great curiosity and attracted even the likes of Nobel laureate Amartya Sen.” Sen wrote in the visitors’ book: “What a wonderful site, really thrilling! And so skillfully excavated and restored.”

“We have found the courtyard that might have been an extension of the platform Hiuen Tsang had described,” Nand Gopal, camp in-charge at the Telhara site, says, peering into his optical line meter that’s mounted on a tripod.

In more recent times, it was A M Broadley, then magistrate of Nalanda, who in 1872 wrote about “Tilas-akiya” as a university and site of learning. British army officer and archaeologist Sir Alexander Cunningham, who visited the place between 1872 and 1878, wrote about inscriptions describing “Teliyadhak” as a place that had seven monasteries and which matched Hiuen Tsang’s account. A statue of the 12-armed Avlokiteshwar Buddha found from a Tiladhak site is at the Indian Museum in Kolkata. Perhaps the best known Pala sculpture from Telhara is now in Rietberg Muzeum, Zurich.

Though there was this and more proof that Telhara could be sitting on a glorious past, it wasn’t until December 2009 that the excavations finally began. Telhara panchayat head Awadhesh Gupta claims to have been the one who got things started.

“We all knew Telhara was once a great seat of learning, but nobody did anything to prove it. In 1995, I approached the Congress government requesting that the place be excavated but got no assurance. When Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar visited the site in 2007, I put up this demand once again. The villagers were not happy with me. They thought I should have demanded something more concrete than just the digging of a mound.”

But the mukhiya may have had the last laugh. Villagers now talk about Telhara being part of the Nalanda-Rajgir circuit and how that could bring them jobs and better opportunities. “We hope the site is conserved and clubbed with Nalanda to attract tourists. The site has already given temporary jobs to 70 villagers,” says Anil Kumar, a villager.

It was a useful mound, no doubt.

Experts associated with its excavation are now claiming that the university originated in the Kushan period.

Atul Kumar Verma said that in the recent excavation, archaeologists have found some bricks of very large size (42x36x6.5cm) substantiating that the university belonged to the Kushan period. “Bricks of the Kushan period were quite large from other dynasties, including the Gupta and Pala periods,” said Verma.

While the Kushan period is considered to be 1st century AD, the Gupta dynasty ruled from 3rd to 6th century AD.

MAJOR FINDINGS

SEALS AND SEALING

The recovery of over 100 terracotta seals and sealings from the Gupta and Pala periods provides strong evidence of this being a Buddhist university. Besides seals of the chakra flanked by two deers, other seals have inscription of Buddhist mantras. Seals of Gaj-Lakshmi and flying birds were also found. Some inscriptions that have not yet been deciphered would be sent to Mysore for deciphering.

PLATFORM, TEMPLES

Just above the ashen layer — said to be proof of Turkish general Bakhtiyar Khilji having destroyed the monastery — is the sanctum sanctorum of three Buddhist shrines, each measuring 3.15 square metres. A big platform, found just below this ashen layer, is said to have accommodated over 1,000 monks.

CELLS FOR TEACHERS

The excavation has so far revealed 11 cells of 4 square meters each. It is believed that these were faculty quarters. There is evidence of bricks from the Gupta and Pala periods.

COPPER BELL CHIMES

The excavation revealed several broken pieces of small bells. Parts of molten copper also suggest that the monastery was well-decorated.

CAUTION INSCRIPTION

A stone inscription in Sanskrit (early Nagari script), probably written just before the destruction of the Tiladhak mahavihara, says, “He who tries to destroy this monastery is either a donkey or a bull”. Below the stone inscription are images of the two animals.

FASTING BUDDHA AND VOTIVE STUPA

A miniature terracotta image of a fasting Buddha from the Pala period is a rare find. A six-foot-tall votive stupa from the Pala period suggests the prevalence of Buddhism.

MAURYAN PERIOD

Bone tools and pottery shards of Northern Black Polished Ware points to this being a settlement in the Mauryan period.

STONE SCULPTURES

Among the over 15 stone sculptures found at the site are a red sandstone sculpture of Bodhisatva, Avlokiteshwar, Manjusri and the Buddha in his ‘earth witness’ mudra. A black stone statue of Buddha in abhay mudra (fearless mode) from the Pala period has been found. The red sandstone Bodhisatva sculpture is believed to be from the Gupta period. Some sculptures of Hindu deities such as Uma Maheshwar and Ganesh and Vishnu from the later Pala period were also found. The presence of a Yamantaka sculpture is evidence of Tantric Buddhism at the monastery.

History

India’s first Islamic Mausoleum Was Built on Top of Ancient Hindu Temple

Published

5 years agoon

December 28, 2020By

Vedic Tribe

About 6 km west of Qutab Minar in Delhi, there lies a tomb called Sultan Ghari which is believed to be the final resting place of Prince Nasir’ud-Din Mahmud, the uncrowned eldest son of Sultan Shamsuddin Iltutmish of the Slave Dynasty built in 1231 AD. It was the first Islamic Mausoleum built in India.

However, engraved symbols of animals, Shiva Linga and the Sanskrit inscriptions on ceiling tell a different tale altogether. The beams of the octagonal crypt bear figures of Kamadhenu, the celestial cow and Varaha, the wild boar reincarnation of Lord Vishnu. These two animals were a royal Hindu insignia and considering the ideology of Islam against idols and the immense hatred towards pigs, it is very unlikely that such statues would adorn the inside of a Muslim tomb.

![]()

Iltutmish invaded eastern part of India in 1225 AD which resulted in signing of a treaty between him and Iwaz Khalji, the ruler of Eastern India. After a few successive battles, Prince Nasiru’d-Din Mahmud was appointed governor of Lakhnauti province who later merged the province of Oudh with Bengal and Bihar, gaining him the title of “Malik-us-Sharq” (King of the East) by his father.

The Prince was killed in 1229 AD after a very short rule of 18 months. Grieved by the death of his favourite son, Iltutmish commissioned the Sultan Ghari Tomb. After Iltutmish’s death in 1236, his daughter, Razia Sultana ruled the kingdom until her defeat and death in 1240 AD.

While ASI is pretty much silent on this matter, historians and archaeologists justify these carvings as new buildings being fashioned out of the debris of some Hindu buildings or that the workmen may have been Hindus and would have built the tomb in Hindu style. Their arguments in favor of the tomb fail here because no building worth its name can be build out of old debris and no workman would even dare to fashion a building for which he is hired according to his taste rather than that of the owner’s.

The building is also of an octagonal shape which is another Hindu specialty.

Due to indifference or perhaps purposeful negligence by the government and ASI, we may never know the reality and history of this ancient Hindu temple.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Latest

Seven Vows and Steps (pheras) of Hindu Wedding explained

Views: 9,347 Indian marriages are well renowned around the world for all the rituals and events forming part of the...

Sari or Saree is symbol of Indian feminism and culture

Views: 7,514 One of the most sensual attires of a woman in India is undoubtedly the sari. It is a...

Atithi Devo Bhava meaning in Hinduism and India

Views: 7,296 Atithi Devo Bhava, an ancient line taken from the Hindu scriptures and was originally coined to depict a visiting person whose...

Sanskrit Is More Than Just A Method To Communicate

Views: 5,450 -By Ojaswita Krishnaa Chaturvedi anskrit is the language of ancient India, the earliest compilation of sound, syllables and...

Significance of Baisakhi / Vaisakhi

Views: 6,689 Baiskhi is also spelled ‘Vaisakhi’, and is a vibrant Festival considered to be an extremely important festival in...

Navaratri: The Nine Divine Nights of Maa Durga!

Views: 7,779 – Shri Gyan Rajhans Navratri or the nine holy days are auspicious days of the lunar calendar according...

History of Vastu Shastra

Views: 11,052 Vastu Shastra (or short just Vastu) is the Indian science of space and architecture and how we may...

Significance of Bilva Leaf – Why is it dear to Lord shiva?

Views: 10,691 – Arun Gopinath Hindus believe that the knowledge of medicinal plants is older than history itself, that it...

Concept of Time and Creation (‘Brahma Srishti’) in Padma Purana

Views: 10,954 Pulastya Maha Muni affirmed to Bhishma that Brahma was Narayana Himself and that in reality he was Eternal....

Karma Yoga – Yog Through Selfless Actions

Views: 9,803 Karma Yoga is Meditation in Action: “Karma” means action and “yoga” means loving unity of our mind with...

Pingback: On Remembrance Day India’s contribution to WW2 has been ignored | Vedic Tribe