Vedic Science

Dhanurveda: The Vedic Military Science

Published

5 years agoon

By

Vedic Tribe

Anyone familiar with the great epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata can clearly notice that martial arts and various combat displays have been vital to the history and cultures of South Asia since ancient times.

In Bhagavad-Gita, Krishna’s discourse to Arjun focuses on a Kshatriya’s action and his duty to take up arms for righteousness, even against his own relatives. In both the epics, there are elaborate details on the acquisition, the use of their skills and powers acquired by the heroes both by human or divine methods to defeat their enemies. They accomplished perfection of these martial techniques under the tutelage of great gurus like Dronacharya and also practicing and perfecting austerities and meditation techniques. Part of their skills also included magical powers received as a gift or a boon from a god or divine powers.

Several different types of martial arts mastery co-existed side-by-side. The epics showcase Arjuna making use of his accomplishments in single-point focus or with powers acquired through meditation. In stark contrast to this, Bhima depended on sheer brute strength to crush his foes.

Of all the warfare tactics, the Dhanurveda was considered to be the highest or best amongst the various weapons traditionally practiced by martial artists in ancient India. The word Dhanurveda in Sanskrit literally means science (veda) of archery (dhanus).

“Battles [fought] with bows [and arrows] are excellent, those with darts are mediocre, those with swords are inferior and those fought with hands are still inferior to them” (Gangadharan, 1985, 645).

The earliest surviving text on dhanurveda is a collection of chapters in the encyclopedic “Agnipurana” that has been dated to 8th Century CE. However, several historians such as G.N. Pant have argued that the earliest versions of a dhanurveda text dates from the period prior to or at least contemporary with the epics (c. 1200–600 BCE; Pant, 1978, 3–5; Chakravarti, 1972, x). Dhanurveda has been described as one of the traditional 18 branches of knowledge in the Vishnupurana.

“Elsewhere, [Dhanurveda] is said to be an Upaveda of Yajurveda, ‘by which one can be proficient in fighting, the use of arms and weapons and the use of battle-arrays …’ Further, it is described as having a sūtra like other Vedas, and as consisting of four branches (catuspāda) and ten divisions (daśavidha)” (Chakravarti, 1972, x).

The chapters found in Agnipurana emphasize on a wide range of techniques and instructions geared towards the king preparing for war whose sole focus is on training his soldiers in arms. These four chapters appear to be an edited version of earlier manuals on the subject of dhanurveda. The later version of Brats Sarngadhara Paddhati, a 15th Century treatise in Sanskrit on the “Science of Horn Blow” is a far more comprehensive book than the Agnipurana, elaborating further on the art of dhanurveda.

“This book contains ideas of people who are masters at bow and arrow. With practice one becomes an expert and can kill enemies” (BrSrPad. 1717; trans. Pant, 1978).

These four chapters focus primarily on how the martial artist trains both his mind and body in use of the most “excellent” bow and arrow. Elsewhere in the Agnipurāna, disparate passages include information on:

- Rituals performed by Brahman priests to protect and/or cause success in battle (Dutt Shastri, 1967, 539, 840),

- Construction of forts (Shastri, 1985, 576–578),

- Instructions for military expeditions (Shastri, 1985, 594), and

- Battle formations and troop deployments (Shastri, 1985, 612–615, 629–635).

The chapters provide both sacred knowledge (paravidya) and profane knowledge (aparavidya) of the subject. Initial pages catalogue the subject, providing five training divisions for warriors on:

- Chariots

- Elephants

- Horseback

- Infantry, and

- Wrestling

There are five types of weapons to be learned that were:

- Projected by machines (arrows or missiles)

- Thrown by hand (spears)

- Cast by hands yet retained (noose)

- Permanently held in the hands (sword) and the hands themselves

The book states that it was the birthright of a Brahman or a Kshatriya to teach dhanurveda to others. The Sudras and people of “mixed castes” could also be called upon by the King to take arms when necessary if they had acquired a general proficiency in the art of warfare by regular training and practice. (AgP. 249.6–8; Dutt Shastri, 1967, 894–895).

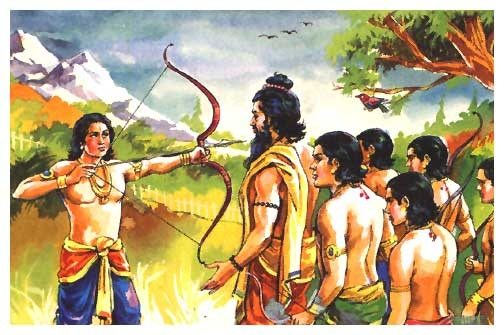

Training in the book starts with the noblest of weapons of bow and arrow, focusing on the specifics of training and practice. It provides the names and describes ten basic lower-body poses to be assumed when using bow and arrow and the specific posture to assume when the disciple pays obeisance to his preceptor (AgP. 249.9–19). Once the basic positions have been described, the manual records technical instructions on how to string, draw, raise, aim, and release the bow and arrow, and it catalogues types of bows and arrows (AgP. 249.20–29).

Second chapter records the more advanced and difficult bow-and-arrow techniques as well as ritual purification of the weapons before they are used. It also discusses the importance of the martial artist achieving the type of subtle state of interior mental accomplishment necessary to become a skilled master. When the archer has become so well practiced that he “knows the procedure,” he is instructed to “fix his mind on the target” before releasing the arrow (Shastri, 1985, 648).

Having achieved the ability to fix his mind, the archer’s training is still not complete. The archer must apply this ability while performing increasingly difficult techniques, such as hitting targets above and below the line of vision, vertically above the head, and while riding a horse; hitting targets farther and farther away; and finally hitting whirling, moving, or fixed targets one after the other (AgP. 250.13–19). The chapter concludes with a summary state of the accomplished abilities of the archer:

“Having learned all these ways, one who knows the system of karma-yoga [associated with this practice] should perform this way of doing things with his mind, eyes, and inner vision since one who knows [this] yoga will conquer even the god of death” (Dasgupta, 1986).

Conquering the “god of death” is akin to conquering the self and overcoming all obstacles, whether physical, mental or emotional but it is not the final training for the archer.

“Having acquired control of the hands, mind, and vision, and become accomplished in target practice, then [through this] you will achieve disciplined accomplishment (siddhi)” (Dasgupta, 1986).

Remainder of the last two chapters focus on postures and techniques for using a variety of other weapons such as:

- Noose

- Swords

- Armors

- Iron dart

- Club

- Battle axe

- Discus

- Trident, and

- Wrestling

The end of final chapter concerns with the use of war elephants and men, concluding with a description of how to send off the fighter to war:

“The man who goes to war after worshipping his weapons and the Trailokyamohan Sastra [one which pleases the three worlds] with his own mantra [given to him by his preceptor], will conquer his enemy and protect the world” (Dasgupta, 1986).

The dhanurvedic tradition was a highly developed system of training through which the martial practitioner was able to achieve a state of ideal perfection and superior self-control, mental calm, single-point concentration and access to special powers in the use of combat weapons. These traits can still be seen today in martial arts such as Kalarippayattu and Manipuri Thangta.

Tamil Martial Arts:

From 4th Century BCE to 600 CE, martial arts predominated across Southern India. During this era, the three kingdoms of Chera, Chola and Pandiya were at a constant struggle for supremacy and domination.

In the Puranānūru (Four Hundred Poems on War) the poetess Ponamutiyār wrote concerning the young warriors of the period,”it is my prime duty to bear and bring him up, it is his father’s duty to make him a virtuous man … it is the duty of the blacksmith to provide him with a lance; it is the duty of the king to teach him how to conduct himself (in war). It is the son’s duty to destroy the elephants and win the battle of the shining swords and return (victorious)” (Subramanian, 1966, 127).

The heroes of this period were noble ones whose main pursuit was fighting with their greatest honour of dying a battlefield death; war was considered a sacrifice of honour and memorials erected for the fallen king, soldiers and their horses.

Power Play of Ancient India:

What is implicit in both early Tamil and Sanskrit sources is the view that combat is not simply a test of overt strength and/or will between two human beings like modern sport boxing, but rather is a contest between a host of complex, contingent, unstable, and immanent “powers” to which each combatant gains access through a variety of means:

- by attaining mastery of a particular technique or weapon through long-term

- practice under the guidance of a guru ;

- by attaining accomplishment (siddhi) in specific meditation techniques giving the practitioner “mental power”;

- by attaining accomplishment in specific mantra that unlocks specific special powers; and/or

- by attaining “power” through a divine gift.

The agency and power of the martial artist in Indian antiquity must be understood as a complex set of interactions between humanly acquired techniques of virtuosity (the human microcosm) and the divine macrocosm.

Unlike today’s commonplace assumptions that any type of power (electricity, gravity, etc.) is stable and therefore measurable and quantifiable, “power” was until recently considered unstable, capricious, and locally immanent. Given this instability, the martial practitioner accumulated numerous different “powers” through any/all means at his disposal, depending not only on his own humanly acquired skills achieved under the guidance of his teacher(s), but also on the acquisition of powers through magico-religious techniques such as repetition of mantra.

The epic literature reflects this complex interplay between divinely gifted and humanly acquired powers for the martial practitioners of antiquity that is clearly part of the dhanurvedic tradition. One example is the playwright Bhāsa’s version of Karna’s story, Karnabhāra (The Burden of Karna), which illustrates the divine gift of power (śakti) that requires no attainment on the part of the practitioner. Indra, disguised as a Brahman, has come to Karna on his way to do combat with the Pāndavas. As a Brahman, Indra begs a gift from Karna.

Karna freely offers gift after great gift, all of which are refused. Finally, against the advice of his charioteer Śalya, he offers that which provides him as a fighter with magical protection – his body armor, which cannot be pierced by gods or demons, and his earrings. Indra joyfully takes them. Moments later a divine messenger informs Karna that Indra is filled with remorse for having stripped him of his protection.

The messenger asks Karna to “accept this unfailing weapon, whose śakti is named Vimalā, to slay one among the Pāndavas” (KarBh. 102; Dasgupta, 1986). At first Karna refuses, saying that he never accepts anything in return for a gift; however, since this gift is offered by a Brahman, he agrees to accept it. As he takes the weapon from the messenger, he asks, “When shall I gain its power (śakti)?” and the messenger responds, “When you take it in [your] mind, you will [immediately] gain its power” (KarBh. 105–106; Dasgupta, 1986). Unlike the powers gained through practice and repetition of exercises or austerities, here Karna is a vehicle of divine power that simply requires that he “take [the weapon] in mind” for its specific power to be at his disposal.

A more complex set of circumstances is at play in the story of Arjuna and the pāśupata weapon, recorded in the Āranyakaparvan (The Book of the Forest) of the Mahābhārata (MBh. 38.1–42.1; trans. Van Buitenen, 1975, 296–303).

His mastery of the weapon requires much more of him than simply accepting the weapon as a gift. Yudhisthira knows that, should combat come, the Kauravas have gained access to “the entire art of archery,” including “Brahmic, Divine, and Demonic use of all types of arrows, along with practices and cures.” The “entire earth is subject to Duryodhana” due to this extraordinary accumulation of powers. Yudhisthira, therefore, calls upon Arjuna to go and gain access to still higher powers than those possessed by the Kauravas.

Yudhisthira is prepared to send Arjuna to Indra, who possesses “all the weapons of the Gods.” But to gain access to Indra, Yudhisthira must teach Arjuna the “secret knowledge,” which he learned from Dvaipāyana and which will make the entire universe visible to him. After Arjuna is ritually purified to win divine protection and once “controlled in word, body, and thought,” he meets Indra in the form of a blazing ascetic who attempts to dissuade him from his task; however, he is not “moved from his resolve” and requests that he learn from Indra “all the weapons that exist.” Indra sends Arjuna on a quest – he can receive such knowledge only after he has found “the Lord of the Beings, three-eyes, trident-bearing Śiva.”

Setting out on his journey “with a steady mind,” he travels to the peaks of the Himalayas, where he settles to practice “awesome austerities.” Eventually Śiva comes to test him in the form of a hunter. After a prolonged fight with bows, swords, trees, rocks, and fists, Śiva subdues Arjuna when he “loses control of his body.” Śiva then reveals his true form to Arjuna, who prostrates before him. Śiva recognizes that “no mortal is your equal” and offers to grant him a wish. Arjuna requests the pāśupata – the divine weapon.

Śiva agrees to give him this unusual weapon, which is so great that “no one in all the three worlds (the Brahmic, Divine, and Demonic) . . . is invulnerable to it.”

To gain access to the weapon’s awesome power, Arjuna must first undergo ritual purification, prostrate himself in devotion before Lord Śiva and embrace his feet, and then learn its special techniques. Śiva instructs him in the techniques specific to the pāśupata, and having become accomplished in these, he also learns “the secrets of its return.”

As illustrated in this and other stories, among all the martial heroes of the epics, Arjuna is the perfect royal sage, possessing the ideal combination of martial and ascetic skills, and able to marshal the various powers at his command as and when necessary. Arjuna is able to attain the awesome power of the pāśupata because of his extraordinary “steadiness of mind,” his superior skills at archery, and his ability to undergo “awesome” austerities.

You may like

-

Seven Vows and Steps (pheras) of Hindu Wedding explained

-

Atithi Devo Bhava meaning in Hinduism and India

-

Navaratri: The Nine Divine Nights of Maa Durga!

-

History of Vastu Shastra

-

Significance of Bilva Leaf – Why is it dear to Lord shiva?

-

Concept of Time and Creation (‘Brahma Srishti’) in Padma Purana

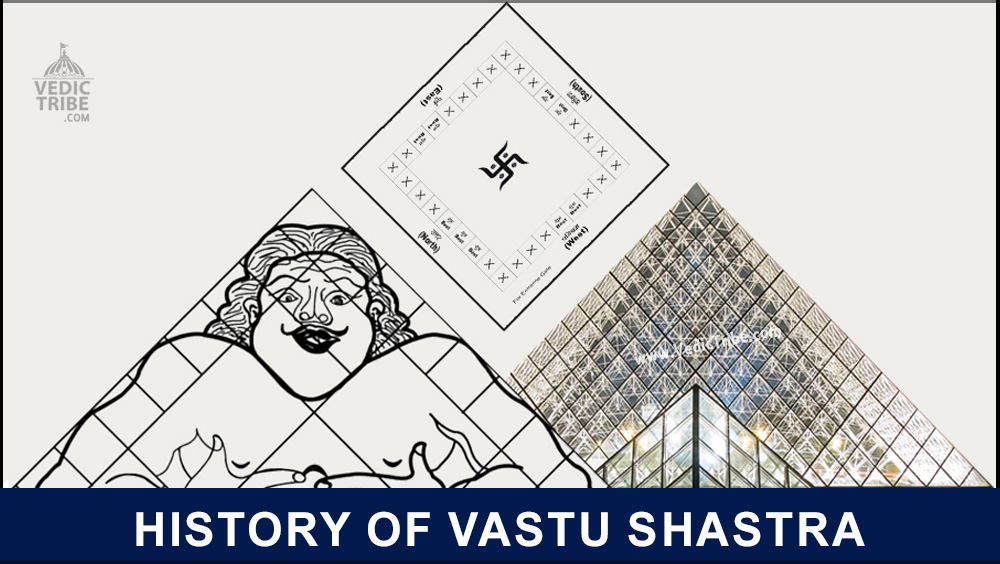

Vastu Shastra (or short just Vastu) is the Indian science of space and architecture and how we may create spaces and environment that supports physical & spiritual health and prosperity.

Vastu Shastra evolved during Vedic times in India. The concept of Vastu Shastra was transferred to Tibet, South East Asia and finally to China and Japan where it provided the base for the development of what is now known as Feng Shui.

Vastu Shastra is the art and science of designing houses, offices, temples etc that swirl with good energy. Indian Maharajas and Moghul Emperors used Vastu Shastra when they built their symmetrical palaces, artificial lakes, and geometric courtyards that thirstily absorbed positive energy.

Like feng shui, Vastu Shastra is based on an octagon with the four directions being the anchors. Hindus believe that gods live in each of the quarters of the house, and govern the rooms, possessions, and activities in these locations.

Vasthu is an inherent energy concept of science. We cannot see energy with our naked eyes but we can realize and see its application in different forms and fashions. Vastu Shastra uses the forces of natural energies and aims to restore the balance between the home (the microcosm) and the cosmos (the macrocosm).

Vastu Shastra is not only a science, but is a bridge between man and nature, thus teaching us the Art of Living. Just like every subject of human aspect is governed with rules, regulations and acts, similarly the nature has also got certain key factor principles for smooth governing of its residents, in which Vastu Shastra stands for the law of natural energies.

Vastu, which literally means to live, works on the premise that the earth is a living organism, out of which other living organisms emerge. This life energy is known as Vaastu Purusha. The Vastu Shastra works for a bounded premise i.e., a house, building, industrial area or shop. The main aim is to form a balance between the outside atmosphere and the atmosphere within the premise. Vastu Shastra makes use of five elements – prithvi (earth), agni (fire), tej (light), vayu (wind) and akash (ether), the earth’s magnetic fields i.e. the north and the south pole and the sun’s rays.

History of Vastu Shastra

Vastu Shastra dates back to the times when the sages lived – probably 6,000 and 3,000 BC. The mention of Vastu Shastra can be found in ancient scriptures like the Rigveda, Atharvaveda, Ramayana, Mahabharata, Mayamatam, Manasa saar, etc. Ancient Indian architecture depended on this science for the building of almost all the palaces and temples. Although the exact origins of Feng Shui are debatable, it is thought to have originated about five thousand years ago. Scholars have recorded various aspects of Feng Shui as early as the Song Dynasty (960 BC). However, the basic principles of Feng Shui were first written down during the Han dynasty (25 AD).

How Vastu Shastra works

Vastu Shastra works on three principles of design that cover the entire premise. The first one is Bhogadyam, which says that the designed premise must be useful and lend itself to easy application. The second is Sukha Darsham, in which the designed premise must be aesthetically pleasing. The proportions of the spaces and the material used, in the interiors and exteriors of the building – ornamentation, colour, sizes of the windows, doors and the rooms and the rhythms of projection and depressions – should be beautiful. The third principle is Ramya, where the designed premise should evoke a feeling of well being in the user.

Also, Vastu Shastra is a complicated form of science put together by seventeen sages. There are certain rules that should be followed while building a house or a building. For instance, the building’s underground water tank or well should be situated in the northeast direction. But, if the building has an overhead tank then it should be placed in the southwest direction. Also, more space should be left to the north and the east of the building compound and less on the south and the west. Open space should be kept around the building and if the plot has a road on the east-north directions, it is better for the inhabitants.

Some short principles of Vastu Shastra

-

Indra, the god of gods, is positioned to the East. The East is where it all begins in Vastu Shastra. When people build their homes, the main door or the entrance is always facing the East. The eastern direction is the harbinger of good luck, which comes into the house through the door.

-

Kubera, the god of wealth, resides in the north. In this location some symbolic valuables should be placed to attract wealth.

-

The Northeast is the position for Dharma, the god of righteousness. In Vastu Shastra, this is the place for worship, meditation and introspection.

-

Agni, the god of fire, lives in the southeast corner. This should be the place of the kitchen.

-

Yama, the god of death, resides in the South. He prevents the evil eye from taking control of our lives. In India, people put a ghoulish pumpkin mask, similar to Halloween masks, in Yama’s position to ward off the evil eye.

-

Niruthi, who prevents homes from being robbed, dwells in the southwest corner.

Vedic Science

Description of Solar Eclipse in the Rig Veda

Published

5 years agoon

February 11, 2021By

Vedic Tribe

India is rich not only in its culture and traditional values but also in the vast knowledge ancient Vedic scriptures have to offer.

Among the four Vedas, the Rig Veda is the oldest. The others are Yajur, Sama and Atharva. They are a compilation of suktas or hymns from many different Sages over a vast span of historical time which is evident by different astronomical reference presented. Rishi Ved Vyas bundled these various hymns into different groups much after their creation.

It is in Rig Veda that Rishi Atri, the human son of Brahma, speaks of eclipses in metaphors of demons and devas.

In Chapter 5, Hymn 40 the Sage explains:

यत तवा सूर्य सवर्भानुस तमसाविध्यद आसुरः |

yat tvā sūrya svarbhānus tamasāvidhyad āsuraḥ |

O Sūrya, when the Asura’s descendant Svarbhanu, pierced thee through and through with darkness

अक्षेत्रविद यथा मुग्धो भुवनान्य अदीधयुः ||

akṣetravid yathā mughdho bhuvanāny adīdhayuḥ ||

All creatures looked like one who is bewildered, who knoweth not the place where he is standing.

सवर्भानोर अध यद इन्द्र माया अवो दिवो वर्तमाना अवाहन |

svarbhānor adha yad indra māyā avo divo vartamānā avāhan |

What time thou smotest down Svarbhanu’s magic that spread itself beneath the sky, O Indra,

गूळ्हं सूर्यं तमसापव्रतेन तुरीयेण बरह्मणाविन्दद अत्रिः ||

ghūḷhaṃ sūryaṃ tamasāpavratena turīyeṇa brahmaṇāvindad atriḥ ||

By his fourth sacred prayer Atri disoovered Sūrya concealed in gloom that stayed his function.

मा माम इमं तव सन्तम अत्र इरस्या दरुग्धो भियसा नि गारीत |

mā mām imaṃ tava santam atra irasyā drughdho bhiyasā ni ghārīt |

Let not the oppressor with this dread, through anger swallow me up, for I am thine, O Atri.

तवम मित्रो असि सत्यराधास तौ मेहावतं वरुणश च राजा ||

tvam mitro asi satyarādhās tau mehāvataṃ varuṇaś ca rājā ||

Mitra art thou, the sender of true blessings: thou and King Varuṇa be both my helpers.

गराव्णो बरह्मा युयुजानः सपर्यन कीरिणा देवान नमसोपशिक्षन |

ghrāvṇo brahmā yuyujānaḥ saparyan kīriṇā devān namasopaśikṣan |

The Brahman Atri, as he set the press-stones, serving the Gods with praise and adoration,

अत्रिः सूर्यस्य दिवि चक्षुर आधात सवर्भानोर अप माया अघुक्षत ||

atriḥ sūryasya divi cakṣur ādhāt svarbhānor apa māyā aghukṣat ||

Established in the heaven the eye of Sūrya, and caused Svarbhanu’s magic arts to vanish.

यं वै सूर्यं सवर्भानुस तमसाविध्यद आसुरः |

yaṃ vai sūryaṃ svarbhānus tamasāvidhyad āsuraḥ |

The Atris found the Sun again, him whom Svarbhanu of the brood

अत्रयस तम अन्व अविन्दन नह्य अन्ये अशक्नुवन ||

atrayas tam anv avindan nahy anye aśaknuvan ||

Of Asuras had pierced with gloom. This none besides had power to do.

The Sage describes how Svarbhanu created eclipses of the Sun and Moon and how Sun appears after an eclipse in the sky.

Svarbhanu is Sva+Bha+Anu.

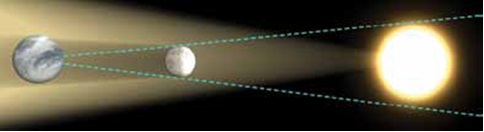

Sva means sky. Bha means light. Anu means follower. Compiled together it means follower of light that is present in the sky. This phenomenon of eclipse is seen due to this shadow where the word Asura stands for the shadow of the moon and not a demon.

Rig Veda says that Svarbhanu was not from the heaven but from the earth, which explains that the moon is a natural satellite of the earth and that it does not have its own brightness but rather reflects the light of the sun.

As shadow of the moon starts covering a large part of the sun, the red tinge of the solar chromosphere becomes visible which is described as the red sheep by Rishi Atri.

When the full solar eclipse takes effect, only the corona can be seen. This is described as the colour of silver sheep. When the eclipse is completely over, the sun is restored to its original bright lustre which is described as the colour of white sheep.

In the fifth stanza tells of all the creatures being frightened and in a terrible condition during the full solar eclipse. The Sage explains that the darkness at the time of this eclipse is different from the normal darkness of the night. The most affected by this darkness are the birds and animals.

It is a well known fact that India’s rich Vedic tradition has had a powerful influence in the field of astronomy and many eclipse events are well documented in the ancient scriptures.

(English translation of the Vedas by Ralph Griffith)

Vaastu Shastra

Vastu for Pooja Room in Home for Positive Energy

Published

5 years agoon

February 5, 2021By

Vedic Tribe

In the present times, Vastu Shastra is the most commonly used term, especially when it comes to purchasing or constructing a new home. To have a happy and prosperous household you must lay stress on enhancing the positive energy inside your home. Vastu Shastra increases wealth, well being and prosperity if you live in structures that allow positive cosmic forces.

One of the most important and sacred corner in any home is a zone of tranquility, the prayer or meditation area; usually known as ‘Pooja Ghar’. Although placement of a Puja Ghar itself brings positive energies in a home, but designing this sacred place as per Vastu guidance enhances positivity in the environment all around. According to Vastu Shastra, the North East zone or the Eeshan (Ishan) corner of a house is the best suited area for placing the Puja room.

It is believed that when Vastu Purush was brought down to the earth, his head laid in the north-east direction. So, while worshipping in this direction along with coming closer to the deity, we also pay obeisance to him. The direction also receives the purifying rays of the rising sun, which purifies the environment and brings positivity and prosperity into our homes.

Follow the below mentioned attributes in order to get an ideal Puja room:

- Never locate the Puja room in the south and the south-east, as these directions are ruled by Yama and Agni, respectively.

- Never locate the Puja space in the bedroom, as this place is for rest and pleasure. However if there is no choice, locate it in the north-east corner of the room. Take care that your feet do not point towards this corner while lying on the bed.

- Avoid locating the toilet above, below or opposite to this room to prevent the negative energies of the toilet from spoiling the auspicious atmosphere of the Puja room.

- This room should also not be constructed next to the kitchen or located under a staircase. In case you do make the Puja space in the kitchen, keep the deity in such a way that you face east while praying.

- In very big plots, factories or apartments, the prayer room can be located in the centre or the Brahmasthana, the sector governed by Lord Brahma, the Creator.

- Make the roof of the Puja room dome or pyramid-shaped. This facilitates smooth flow of positive energies from the tip to the dome or pyramid into the puja room. This shape also assists in meditation.

- Use tranquil colours on the walls of the Puja room like white, soft shades of yellow, blue or violet. These colours do not distract while praying.

- Ideally, the doors and windows of this room should open towards the east or north. These should be made of good quality wood and have double shutters.

- Although north-east is generally the direction recommended for locating the idols or pictures of various Gods; yet different deities have different auspicious locations as described:

- Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesh, Kartikeya, Indra and Surya are placed in the east and facing towards west.

- Ganesh, Durga, Kuber, Shodas Matrika and Bhairav in the north direction and facing south.

- Hanuman in the north-east facing south-west, but never in the south-east as it creates fire hazard.

- Never keep idols brought from ancient temples in the puja room. Also avoid Shrichakra and Shaligram idols, unless you have tremendous spiritual control and are capable of performing puja in a traditional manner.

- Never display photographs of the dead family members along with the deities.

- The height of idols should not be more than 18 inches and should always be placed on a high platform or singhasan.

- Keep the holy books or dharmic granths and other items of samagri and dresses of the deities along the west and south wall.

- The lamp or deepak should be placed in the south-east direction, governed by Agni.

- The Puja room should not be used for other purposes, like storing items that do not belong here. It should also not be used for sleeping purposes or to conceal money and other valuables.

- Never keep a dustbin in the Puja room, as the positive energy gets diminished due to the negative energies emitted by it.

- If you ensure the above mentioned points, you would not only add to the serenity of the room, but would also find yourself spiritually uplifted with increased powers of meditation.

- Dr. Prem Kumar Sharma, resident astrologer of Hindustan Times and Vastu consultant, has authored many books including ‘A Comprehensive Book on Vastu’ and ‘Cultivate Your Relationship the Vastu Way’.

~ By Astrologer Dr. Prem Kumar Sharma

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Latest

Seven Vows and Steps (pheras) of Hindu Wedding explained

Views: 9,601 Indian marriages are well renowned around the world for all the rituals and events forming part of the...

Sari or Saree is symbol of Indian feminism and culture

Views: 7,707 One of the most sensual attires of a woman in India is undoubtedly the sari. It is a...

Atithi Devo Bhava meaning in Hinduism and India

Views: 7,531 Atithi Devo Bhava, an ancient line taken from the Hindu scriptures and was originally coined to depict a visiting person whose...

Sanskrit Is More Than Just A Method To Communicate

Views: 5,586 -By Ojaswita Krishnaa Chaturvedi anskrit is the language of ancient India, the earliest compilation of sound, syllables and...

Significance of Baisakhi / Vaisakhi

Views: 6,808 Baiskhi is also spelled ‘Vaisakhi’, and is a vibrant Festival considered to be an extremely important festival in...

Navaratri: The Nine Divine Nights of Maa Durga!

Views: 7,877 – Shri Gyan Rajhans Navratri or the nine holy days are auspicious days of the lunar calendar according...

History of Vastu Shastra

Views: 11,253 Vastu Shastra (or short just Vastu) is the Indian science of space and architecture and how we may...

Significance of Bilva Leaf – Why is it dear to Lord shiva?

Views: 10,912 – Arun Gopinath Hindus believe that the knowledge of medicinal plants is older than history itself, that it...

Concept of Time and Creation (‘Brahma Srishti’) in Padma Purana

Views: 11,163 Pulastya Maha Muni affirmed to Bhishma that Brahma was Narayana Himself and that in reality he was Eternal....

Karma Yoga – Yog Through Selfless Actions

Views: 9,958 Karma Yoga is Meditation in Action: “Karma” means action and “yoga” means loving unity of our mind with...