Bharat

The Great Wall of India – Kumbhalgarh, Mewar (UNESCO)

Published

5 years agoon

By

Vedic Tribe

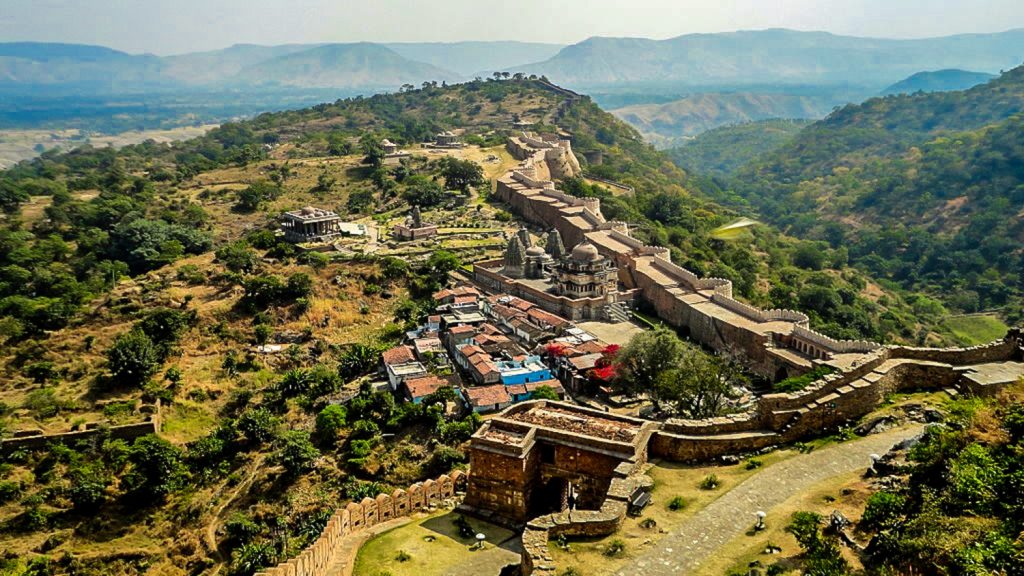

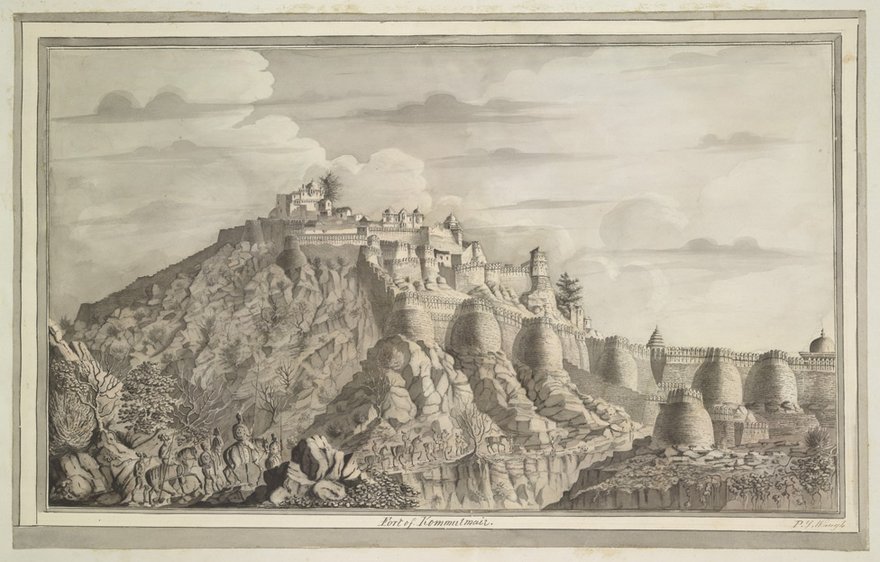

The walls have seven gateways and they are over fifteen feet wide in some places protecting over 360 temples from invaders. Kumbhalgarh is a Mewar fortress and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the Aravalli Hills, in the Rajsamand district in western India.

We have all heard of the Great Wall of China, but few know that India also has its own “Great Wall of India”, that has been long overshadowed by its neighbour to the East. Commonly called after the fort it surrounds, Kumbhalgarh, it is almost unknown outside its region.

The wall extends for 36kms and can easily be mistaken for the Great Wall of China if viewed at through photographs. Contrary to the latter, however, work on Kukbhalgarh began in 1443, separating the two not only through locations and cultures but many centuries as well.

The fort was built during the 15th century by Rana Kumbha, the ruler of the Mewar kingdom of western India. Out of the 84 forts in his dominion, Rana Kumbha is said to have built 32 of them, of which Kumbhalgarh is the largest and most elaborate. He ordered the work to begin on this wall, originally meant to surround and protect his fort high on a hill, about 1000 meters above sea level. It was later enlarged in the 19th century and the place is now a museum. The walls have seven gateways and are over fifteen feet wide in some places. The inhabitants of Kubhalgarh, the fertile land and over 360 temples behind these walls were protected from any outside danger. The temples were built by followers of the three major religions of India: Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

Legend has it that despite several attempts, the wall could not be completed for one reason or the other. Finally the king consulted one of his spiritual advisers and was advised that a sacrifice be made, and a volunteer offered his life so that others will be protected. Today, the main gate stands where his body fell and a temple where his severed head came to rest. The fortress behind the walls only fell once over the course of its five hundred years of history, but only because drinking water ran out within its walls.

The present fort is built on a hilltop 1,100 m (3,600 ft) above sea level on the Aravalli range, the fort has a perimeter wall that extends 36 km (22 mi), making it one of the longest walls in the world (described as the “Great Wall of India”) with seven fortified gateways.

From its strategic position, it is possible to see many miles into the Aravalli Range and the sand dunes of the Thar Desert. With frontal walls measuring fifteen feet thick, the fort remained almost impregnable to direct assault despite multiple failed sieges.

Ahmed Shah I (ruler of the Muzaffarid dynasty, who reigned over the Gujarat Sultanate) attacked the fort in 1457 but found the effort futile. There were further failed attempts in 1458–59 and 1467 by Mahmud Khalji (a 15th-century sultan of the Malwa Sultanate).

The general of Akbar, Shabhbaz Khan, is believed to have taken control of the fort in 1576. But it was recaptured by Maharana Pratap in 1585. Finally in 1615 the Mewar kingdom surrendered against the Mughal forces sent by Emperor Jahangir under the command of Prince Khurram where it took the combined armies of Delhi, Amber, and Marwar to breach its defences by poisoning the forts water supply.

Among the internal buildings, are the ruins of the palace complex, over 360 temples, 300 ancient Jain (Jainism, traditionally known as Jain Dharma, is an ancient Indian religion) and the rest Hindu.

The fort remained occupied till the 19th century when it was taken over by the British and later returned to Udaipur State.

Tourists visiting these grounds are warned of ancient defense mechanism and traps, although most of them have been disabled. This beautiful monument to history however still remains much of a mystery and is almost unknown to the rest of the world outside India.

You may like

~ Bill Aitken

Indian rivers are not just part of epics and religious texts but also guardians of her cultural wealth.

From the beginning of recorded history, India has honored her rivers, both for their beauty and their blessings. Seven of these rivers were singled out for recognition as goddesses, not for their hydrological profile but for the sacred and cultural associations surrounding them.

Ganga: Symbol of purity

First in the list is the goddess Ganga (the Ganges river). Her source at the ice cave of Gaumukh (cow’s mouth) in the Uttarakhand Himalayas must be the most inspiring on our planet for sheer aesthetic grandeur. Not even the epics surrounding the river can match the sublime impact of its physical birth. Starting from the pilgrim site of Gangotri, she flows as river Bhagirathi. It is only on her meeting with Alakananda River at Devprayag that the name Ganga is given.

Then, downstream at Haridwar, the Ganga emerges into the plains where her course to the sea is marked by the confluence at Prayag in Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh. Here Ganga is joined by Yamuna and symbolically by the third goddess, Saraswati. Varanasi is likewise graced by the waters of Ganga Maharani. Of Ganga’s flowing locks that comprise the river’s delta, the Hooghly passing through Kolkata in West Bengal, has the privilege of hosting the final place of pilgrimage at the small island of Ganga Sagar where the goddess, after 2,525 km, merges with the Bay of Bengal.

Yamuna: Bountiful beauty

The source of the second goddess Yamuna, the younger sister of the Ganga, is marked by scalding hot springs at Yamnotri. She rises from the snows of the Bander Poonch massif near Uttarakhand’s border with the state of Himachal Pradesh. While passing near Mussoorie in Uttarakhand, the winding course of the river has an Ashokan edict on its banks extolling the virtues of non-violence. The goddess exits the Himalayas at Paonta Sahib, a Sikh pilgrimage hallowed by the residence of the Sikh Guru Gobind Singh. Its waters help give the state of Haryana in India its name signifying dazzling greenery.

Once it nears New Delhi, the capital of India, the goddess is assailed by urban challenges. Downstream of the capital, the river flows past the ghats at Mathura in Uttar Pradesh where the votaries of Radha and Krishna gather. It curls round the dreamy profile of the Taj Mahal at Agra in Uttar Pradesh, then winds her way through eroded terrain where the Chambal joins her. Finally, before the auspicious meeting of the rivers at Prayag, 1,370 km from her source, the Yamuna is refreshed by the blue waters of the Betwa.

Godavari: Promise of prosperity

Godavari, Ganga’s elder sister, is a non-Himalayan river. Her flow is seasonal. She drains the lesser ranges of Deccan Plateau which receives little precipitation outside the monsoon. Her source is atop the black mesa formations of the north Sahyadri range. At the foot of these mountains is the sacred Trimbakeshwar Temple near the town of Nasik in the state of Maharashtra. The river flows for 1,465 km across almost the width of the peninsula from Nasik in the Western Ghats to cut through the Eastern Ghats leading to Yanam which was a former colonial outpost of Puducherry in Andhra Pradesh.

The small town of Paithan in Maharashtra lay on an ancient trade route and is famous for heavy silk saris. Shirdi is another small town near the Godavari that has become a place of pilgrimage. Downstream is the well-maintained gurudwara at Nander where Sikh Guru Gobind Singh breathed his last. The southeast flow of the river after it leaves Maharashtra for the state of Andhra Pradesh is supplemented by river Manjra from the south and Pranhita and Indrawati from the tribal districts lying to the north. The goddess takes a sharp turn at the Bhadrachalam Temple in Andhra Pradesh before cleaving a passage through the Eastern Ghats. She then descends in a broad southerly flow to the agricultural town of Rajahmundry in the state of Andhra Pradesh which marks the entrance to the fertile delta. Here the Draksharama Temple commanding the Gautam Godavari delivers final blessings before the goddess flows via Yanam into the Bay of Bengal.

Narmada: Auspicious beauty

Narmada, daughter of Lord Shiva, is to many the most beautiful. Her source is at Amarkantak amidst the leafy Maikala Hills of eastern Madhya Pradesh. It then passes through tribal territory thick with bamboo and rich in iron ore. At the medieval fort of Mandla in Madhya Pradesh, the river broadens out. The erstwhile ruling dynasty of the area boasts of being the last to hold out against the Mughal advances. Near Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh are the Dhuandar waterfalls in the fabled marble gorge. The many hues of marble are said to be auspicious for carving temple images.

Large smooth basaltic lingams are also found in Narmada’s bed. Jabalpur lays claim to inventing snooker; it is said to have first been played here in colonial times. Omkareshwar is a scenic island with an ancient Jyotirlinga Temple and in contrast, this pilgrim site is followed downstream by the princely bathing ghats at Maheshwar. These were built by the widowed Holkar queen Ahalya Bai of the Maratha-ruled Malwa kingdom who bravely stood up for her family faith in the face of bigotry. Lower in its course, the river is dammed to form the Sardar Sarovar, a gravity dam near Navagam in Gujarat. Finally, at the estuary town of Bharuch in Gujarat, it flows into the Arabian Sea.

Saraswati: Alive in folklore

The holy river Saraswati is the Hindu goddess of learning. Beautiful to look upon, Saraswati holds the ancient stringed veena and is seated upon a swan. In ancient scriptures, Saraswati was a broad river that used to water what is now the Rajasthan desert. It was discovered under the sand in the 1930s from the remains of the Harappan civilisation. According to satellite imagery, the course of the dried-up river can still be discerned and in Hindu folklore, the Saraswati remains very much alive.

Recently, at Ad Badri in the Shivalik foothills of Haryana, the source of a small river, known as the Sarsutti, has been developed as a pilgrim centre. Both Kurukshetra in Haryana and Pushkar in Rajasthan have lakes associated with this lost sacred river and host huge gatherings of pilgrims on auspicious bathing days. It is assumed that the Saraswati flowed into the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat and then into the Arabian Sea.

Indus: High and mighty

The Indus gave its name to India – foreigners referred to it as the land that lies “beyond the Indus.” Also known as the Lion River, the Indus (or Sindhu) is the largest in the subcontinent, flowing for 3,200 km from undistinguished springs in Tibet, north of Mt Kailash. The flow of the river is determined by season – it diminishes in winter while flooding its banks between July and September.

This mighty river delimits the western end of the Great Himalayan range and the towering height of the Naga Parbat massif at the river’s sharp turn to outflank the mountain astounds all who behold it. From Tibet border, it flows northeast through Leh past the town’s huge and fascinating mud fort. At Nyemo, the Zanskar River joins the Indus at perhaps the most sublime confluence in the Himalayas. The river is worshipped by fishermen downstream in the Pakistan province of Sind where the shallow and sluggish Indus reaches the Arabian Sea.

Kaveri: Guardian of cultural wealth

Goddess Kaveri may be the shortest in length (765 km) but is the guardian of the most scintillating array of India’s cultural wealth. Known as the ‘Ganga of the South’, the goddess is depicted standing wearing a red silk sari and holding a copper water pot from which she pours her blessings. Kaveri (or Cauvery) rises in the hills of Coorg in the Karnataka section of the Western Ghats above the temple at Bhagamandalam. The source is known as Talakaveri and a small tank has been built to receive the overflow from the sacred spring. From the wooded hills of Coorg, the river flows to the confines of Mysore, then past Srirangapatnam in Karnataka where Tipu Sultan had his palace.

On the banks of Kaveri at Talakad near Mysore in Karnataka stands a strange spectacle of medieval temples silted up by the sand and wind. The goddess in her regal mood is seen at the spectacular Shivanasamundra Waterfalls and then again at the dramatic cataracts of Hogenakkal near the border of Tamil Nadu. As she approaches the delta region, the goddess unleashes a display of artistic, architectural and musical wonders. Trichy’s fort, the devotional rendering of Tyagaraj’s songs at Thiruvaiyaru in Thanjavur district in Tamil Nadu, Sriramgam’s extensive godly enclosure, the exquisitely poised bronze images of Cholan figures and Thanjavur’s towering temples and are a few of the living treasures of the delta region. The recognised channel of the Kaveri debouches into the Bay of Bengal near the coast at Poompahar in Tamil Nadu known to Roman traders as Kaveri Emporium.

Bharat

Telhara University – Older than Nalanda, Vikramshila Universities

Published

5 years agoon

December 29, 2020By

Vedic Tribe

It was a useful mound, no doubt. A good vantage point where villagers occasionally relieved themselves.

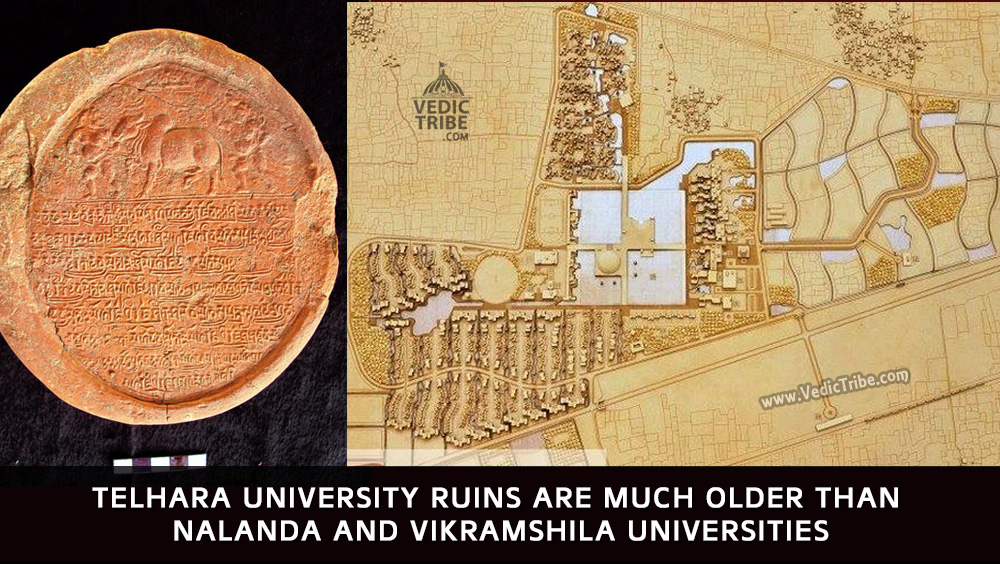

But who would have thought that deep beneath its golden brown earth would be stories of dynasties and empires that now suggest that this — Telhara, a village 33 km from the ruins of the more famous Nalanda University — could be ‘Tilas-akiya’ or ‘Tiladhak’, the place Chinese traveler Hiuen Tsang visited and wrote about during his travels through India in 7th century AD? So far, there were only vague references but recent excavations at the mound suggest that Telhara was indeed an ancient university or seat of learning with seven monasteries.

The Bihar government has been calling the Telhara project one of its biggest after the excavations that unearthed Nalanda and Vikramshila universities. The excavation at Telhara should have happened earlier, say experts, but the site lost out to the more famous Nalanda.

The Telhara project that started on December 26, 2009, has so far come across over 1,000 priceless finds from 30-odd trenches — seals and sealing, red sandstone, black stone or blue basalt statues of Buddha and several Hindu deities, miniature bronze and terracotta stupas and statues and figurines that go back to the Gupta (320-550 AD) and Pala (750-1174 AD) empires. But the 2.6-acre mound has now thrown up the most tantalising find yet — evidence of a three-storied structure, prayer hall and a platform to seat over 1,000 monks or students of Mahayana Buddhism.

The terracotta monastery seals — a chakra flanked by two deers — unearthed at Telhara are similar to those at Nalanda, suggesting Telhara or Tiladhak was another great seat of learning besides Nalanda and Odantpuri during the Gupta and Pala reigns. It was the discovery of a similar monastery seal that clinched it for Nalanda University.

Former Archaeological Survey of India director B S Verma, who between 1971 and ’81 supervised the excavation at the site of the ancient Vikramshila university, says, “Telhara or Tiladhak has much more convincing epigraphical proofs — monastery inscriptions — than Vikramshila. The findings that match Hiuen Tsang’s account do more to convince that the place was a university or mahavihara similar to Nalanda.”

In his book, The Antiquarian Remains in Bihar, historian D R Patil writes about Hiuen Tsang’s description of Telhara. “Hiuen Tsang describes Telhara or Tilas-akiya as containing a number of monasteries or viharas, about seven in number, accommodating about 1,000 monks studying in Mahayan. These buildings, he says, had courtyards, three-storied pavilions, towers, gates and were crowned by cupolas with hanging bells. The doors and windows, pillars and beams have bas relieves (sculptures in guilded copper). In the middle vihara is a statue of Tara Bodhisatva and to the right (is) one of Avlokiteshwar”.

Other history books too talk of Tiladhak monastery, on the western side of Nalanda, as having four big halls and three staircases. It is said the mahavihara or university was built by one of the descendants of Magadha ruler Bimbisara. The monastery was decorated with copper and also had small copper bells that gently chimed in the breeze.

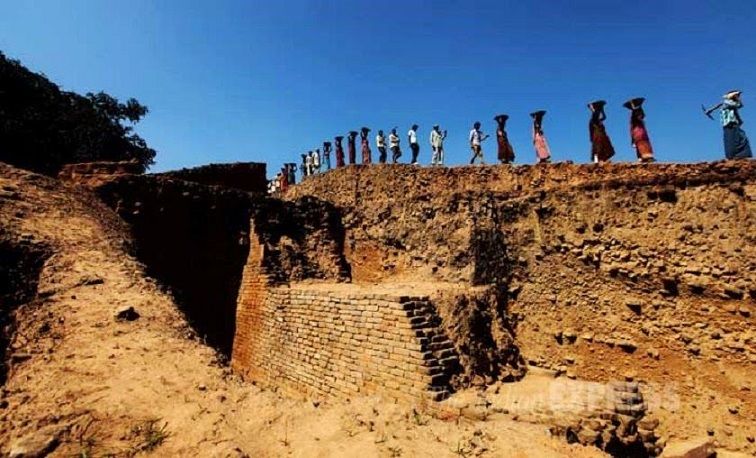

For months now, the excavation has been unearthing these stories. Apart from the mound that is now being dug up, Telhara has six other mounds — five of which have settlements and one which is partially elevated.

Atul Kumar Verma, director (archaeology) of the Bihar government’s Department of Art and Culture, says, “Since the excavations suggest that Telhara might have been a contemporary of Nalanda, it is quite possible that it was either an independent university for specialized education or that students graduating from Nalanda University would come here for specialized study. It is a great feeling to see the place emerging as the next big find after Nalanda. It has also aroused great curiosity and attracted even the likes of Nobel laureate Amartya Sen.” Sen wrote in the visitors’ book: “What a wonderful site, really thrilling! And so skillfully excavated and restored.”

“We have found the courtyard that might have been an extension of the platform Hiuen Tsang had described,” Nand Gopal, camp in-charge at the Telhara site, says, peering into his optical line meter that’s mounted on a tripod.

In more recent times, it was A M Broadley, then magistrate of Nalanda, who in 1872 wrote about “Tilas-akiya” as a university and site of learning. British army officer and archaeologist Sir Alexander Cunningham, who visited the place between 1872 and 1878, wrote about inscriptions describing “Teliyadhak” as a place that had seven monasteries and which matched Hiuen Tsang’s account. A statue of the 12-armed Avlokiteshwar Buddha found from a Tiladhak site is at the Indian Museum in Kolkata. Perhaps the best known Pala sculpture from Telhara is now in Rietberg Muzeum, Zurich.

Though there was this and more proof that Telhara could be sitting on a glorious past, it wasn’t until December 2009 that the excavations finally began. Telhara panchayat head Awadhesh Gupta claims to have been the one who got things started.

“We all knew Telhara was once a great seat of learning, but nobody did anything to prove it. In 1995, I approached the Congress government requesting that the place be excavated but got no assurance. When Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar visited the site in 2007, I put up this demand once again. The villagers were not happy with me. They thought I should have demanded something more concrete than just the digging of a mound.”

But the mukhiya may have had the last laugh. Villagers now talk about Telhara being part of the Nalanda-Rajgir circuit and how that could bring them jobs and better opportunities. “We hope the site is conserved and clubbed with Nalanda to attract tourists. The site has already given temporary jobs to 70 villagers,” says Anil Kumar, a villager.

It was a useful mound, no doubt.

Experts associated with its excavation are now claiming that the university originated in the Kushan period.

Atul Kumar Verma said that in the recent excavation, archaeologists have found some bricks of very large size (42x36x6.5cm) substantiating that the university belonged to the Kushan period. “Bricks of the Kushan period were quite large from other dynasties, including the Gupta and Pala periods,” said Verma.

While the Kushan period is considered to be 1st century AD, the Gupta dynasty ruled from 3rd to 6th century AD.

MAJOR FINDINGS

SEALS AND SEALING

The recovery of over 100 terracotta seals and sealings from the Gupta and Pala periods provides strong evidence of this being a Buddhist university. Besides seals of the chakra flanked by two deers, other seals have inscription of Buddhist mantras. Seals of Gaj-Lakshmi and flying birds were also found. Some inscriptions that have not yet been deciphered would be sent to Mysore for deciphering.

PLATFORM, TEMPLES

Just above the ashen layer — said to be proof of Turkish general Bakhtiyar Khilji having destroyed the monastery — is the sanctum sanctorum of three Buddhist shrines, each measuring 3.15 square metres. A big platform, found just below this ashen layer, is said to have accommodated over 1,000 monks.

CELLS FOR TEACHERS

The excavation has so far revealed 11 cells of 4 square meters each. It is believed that these were faculty quarters. There is evidence of bricks from the Gupta and Pala periods.

COPPER BELL CHIMES

The excavation revealed several broken pieces of small bells. Parts of molten copper also suggest that the monastery was well-decorated.

CAUTION INSCRIPTION

A stone inscription in Sanskrit (early Nagari script), probably written just before the destruction of the Tiladhak mahavihara, says, “He who tries to destroy this monastery is either a donkey or a bull”. Below the stone inscription are images of the two animals.

FASTING BUDDHA AND VOTIVE STUPA

A miniature terracotta image of a fasting Buddha from the Pala period is a rare find. A six-foot-tall votive stupa from the Pala period suggests the prevalence of Buddhism.

MAURYAN PERIOD

Bone tools and pottery shards of Northern Black Polished Ware points to this being a settlement in the Mauryan period.

STONE SCULPTURES

Among the over 15 stone sculptures found at the site are a red sandstone sculpture of Bodhisatva, Avlokiteshwar, Manjusri and the Buddha in his ‘earth witness’ mudra. A black stone statue of Buddha in abhay mudra (fearless mode) from the Pala period has been found. The red sandstone Bodhisatva sculpture is believed to be from the Gupta period. Some sculptures of Hindu deities such as Uma Maheshwar and Ganesh and Vishnu from the later Pala period were also found. The presence of a Yamantaka sculpture is evidence of Tantric Buddhism at the monastery.

Bharat

Macaulay’s Children are still thriving in India

Published

5 years agoon

December 29, 2020By

Vedic Tribe

~ Subhash Kak, Indian American Computer Scientist, Regents Professor and Author

Imprinting is the key that explains many of our peculiarities. Imprinted birds and mammals act as if they were human. Goslings, when reared by a person, become imprinted to the caregiver, and they will ignore geese. Imprinted people live in their own world of symbols, and their behavior to an outsider would appear strange.

Imprinting occurs during a sensitive window of development. Imprinted animals will mate with their own kind but will prefer the animal to which they have been imprinted. In extreme cases they will refuse social contact with their own kind. Imprinting is fixed for life; it occurs also in motor patterns, as in birdsong. Humans are also imprinted— to ideas and beliefs they are exposed to in their childhood.

All this has been known for a long time. Herodotus tells us of how hostage children raised in court became loyal to their captors. In the US, Canada, Australia, the children of the natives were forcibly taken from their parents and put in foster homes for this reason.

The Ottoman Empire built a bizarre but effective system based on this idea. It created the institution of the Kapi Kullari (“Slave” or “Ruling Institution”), whose members were legally slaves of the sultan: they were born Christians but were converted to Islam primarily through the practice of devsirme, where able-bodied young children were recruited as child-tribute and immersed in Islamic culture.

The kullars were forbidden to contract legal marriage, to have acknowledged children, and to own private property. They served solely at the pleasure of the sultan, at whose will they were promoted and executed. The slave status divested the kullars of any personality outside the service of the master.

The kullars as Janissaries were the best regiments of the Ottoman army; they also served in the palace jobs and as provincial governors. The Grand Vizier was invariably a kullar. They constituted a superlative bureaucracy: they were devoted to their duties, were completely loyal and since they were isolated from the general population, they were fair. Their non-hereditary status prevented the formation of a ruling elite that might threaten the sultan.

With time, the kullars began seeking reforms in their inhumane system. By the end of the Empire, they had won the right to matrimony. But as their circumstances changed they became venal; what was their strength as an isolated community now became a license to do good only for themselves.

If the kullars constituted the backbone of the Ottoman Empire, an institution, similar in spirit but somewhat different in form (but more subtle and resilient), was formed to safeguard the British Empire in India. This was the institution of the brown sahib, the colonial apologist, formed under the directive of the famous Minute of Macaulay (1835) who wished to create “a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.” These Indian kullars may be properly called Macaulay’s children.

The central idea in the imprinting of the Indian kullars was Macaulay’s assertion that “a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India.” The British, following Macaulay’s ideas, dismantled the traditional pathshala system of village education, which had provided universal literary to the people. William Adam, a Scottish missionary in Bengal and Bihar during 1835-7, estimated that there were 100,000 pathshalas which were popular with all classes of people, “irrespective of their religion, caste, or social status,” and the “curriculum was designed towards meeting the practical demands of rural society.”

The village school had great room for improvement but it was very effective and was one of the institutions of local power. When it was superseded by the new system, controlled by the British bureaucracy using an alien language whose benefit ordinary people could not see, children of the poorer classes simply pulled out. This led to the illiteratization of the great masses of the Indian population.

The Macaulayite bureaucracy worked against other traditional knowledge also. For example, it targeted the millennia-old system of water tanks, which had been serviced by village councils. In its place was instituted a system of canal irrigation. This was done even where it was unsuitable, and the local councils were disbanded. Soon, the tanks fell into disuse and the water table dropped; this had disastrous effects for agriculture.

In the colonial state, the idea of profit was replaced by that of service of the British empire. The new system of education was instrumental for the socialization of this view. The idea of the other-worldly Indian was promoted.

In 1947, there was hope that India would create a progressive nation-state, but Macaulay’s children quietly seized power. Taught to hate India’s past and lacking a defining center, they took the fashions of the day–such as Socialism and Marxism–, and elevated these to their religious ideology. The terms Socialism and Secularism–but with a perverted meaning–were even written into the Indian Constitution during the Emergency of the mid-1970s.

In awe of the British and insecure of their positions, those of the Macaulay children who went into governance were good administrators. But as the system of checks and balances eroded after independence, they lost their reputation for incorruptibility.

Blind adherence to an ideology can stunt intellectual and emotional growth. Such people are forever seeking approval from those whom they idolize, and they are unable to grasp the incongruity of their behavior. Emotionally stunted people are like imprinted children, who can be very cruel. (The Khmer Rouge massacres of Cambodia, amongst the most horrific of the past century, were carried out principally by teenagers imprinted to one brand of Marxism.) Adults, with the minds of children, also brook no opposition, although their ways may not be as drastic.

The Macaulayite establishment in India is especially intolerant: it also knows a few tricks of Stalin. It silences its opponents using censorship and a system of patronage. But recently, independent minded American-style Internet magazines have provided a means to side-step this censorship.

Take Arun Shourie’s experience: Although India’s most famous and recognized journalist and author, winner of the Magasaysay award, he was black-listed by mainstream publishers and the media as soon he turned his attention to subjects considered taboo by the establishment. During the last ten years he has been compelled to self-publish his books and newspapers have banned him. But thanks to his Internet column he remained hugely popular until he joined the Vajpayee administration as a minister and stopped writing.

Having been black-listed once, his books are still not reviewed, and his speeches as a minister are rarely reported unless his words can be twisted to paint him as a monster. He is like a non-person of the apartheid South Africa. The favorite abusive label to pin on the opponent is to call him “communalist” or “fascist”, and Shourie has carried these labels frequently.

As another example consider Mark Tully, the distinguished British journalist and author, who was for a long time the bureau chief of BBC in Delhi. Just because one of his books was perceived as somewhat critical of the Macaulayites, he was called names and declared a sell-out. His books have also stopped receiving notices.

This is quite unlike the rivalry between the liberals and the conservatives in the West, where the most partisan writers concede that their opponents have the right to be heard through the print and the TV media.

Some have suggested that the current turmoil in India is just a struggle between the traditional and modern approaches to governance. Nothing could be further from the truth. The opponents of the Macaulayites and Marxists do not wish for a religious state. They want to build a modern society somewhat like that of the United States: forward-looking but yet connected to its culture.

Reading the reportage of the culture wars of India by Western journalists in a hurry, one gets the feeling that the only sane people in India are these Macaulay’s children. The reformers are labeled nationalists, swamis, traditionalists, or worse. These journalists do not understand the real nature of the struggle.

It is funny. The West proclaimed a certain imagined view on India, and now its pupils insist this is the real thing, even though there is evidence to the contrary for everyone to see.

Could there be a better case of the tail wagging the dog?

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Latest

Seven Vows and Steps (pheras) of Hindu Wedding explained

Views: 9,634 Indian marriages are well renowned around the world for all the rituals and events forming part of the...

Sari or Saree is symbol of Indian feminism and culture

Views: 7,745 One of the most sensual attires of a woman in India is undoubtedly the sari. It is a...

Atithi Devo Bhava meaning in Hinduism and India

Views: 7,595 Atithi Devo Bhava, an ancient line taken from the Hindu scriptures and was originally coined to depict a visiting person whose...

Sanskrit Is More Than Just A Method To Communicate

Views: 5,616 -By Ojaswita Krishnaa Chaturvedi anskrit is the language of ancient India, the earliest compilation of sound, syllables and...

Significance of Baisakhi / Vaisakhi

Views: 6,834 Baiskhi is also spelled ‘Vaisakhi’, and is a vibrant Festival considered to be an extremely important festival in...

Navaratri: The Nine Divine Nights of Maa Durga!

Views: 7,904 – Shri Gyan Rajhans Navratri or the nine holy days are auspicious days of the lunar calendar according...

History of Vastu Shastra

Views: 11,294 Vastu Shastra (or short just Vastu) is the Indian science of space and architecture and how we may...

Significance of Bilva Leaf – Why is it dear to Lord shiva?

Views: 10,940 – Arun Gopinath Hindus believe that the knowledge of medicinal plants is older than history itself, that it...

Concept of Time and Creation (‘Brahma Srishti’) in Padma Purana

Views: 11,208 Pulastya Maha Muni affirmed to Bhishma that Brahma was Narayana Himself and that in reality he was Eternal....

Karma Yoga – Yog Through Selfless Actions

Views: 9,986 Karma Yoga is Meditation in Action: “Karma” means action and “yoga” means loving unity of our mind with...