Female and Male as Two Halves

Goddess in Worship

Among the four main deity traditions still followed to date, Ganapatya, Vaishnava, Shaiva and Shakta, the feminine divine plays a central role. The Shakta tradition exclusively worships the feminine divine in the form of Shakti or Divine Mother. God as a Mother Goddess is responsible for the well-being of the Universe, and is considered the embodiment of incredible power. Shrines of the Shakta tradition are found all across the Indian subcontinent, unlike some of the male deity traditions, which often times are found in geographically confined regions. Furthermore, even in the male deity traditions, including Shaiva and Vaishnava, Shakti is considered the energy which sustains everything, including the male deities. In fact, such male deities are seen as incomplete without their consorts.

The Feminine in Scripture

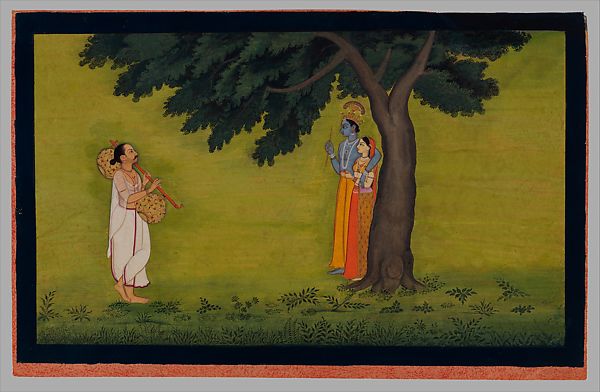

Since ancient times, female figures have featured prominently in Hinduism, both in human and divine form. Many of the sages associated with the realization and authoring of the Vedas were women. The Rig Veda contains hymns composed by women such as Lopamudra and Maitreyi. Sage Gargi appears in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad where she poses a volley of questions to Sage Yajnavalkya on the nature of the soul, and teases out core teachings from Yajnavalkya that a courtroom of male philosophers failed to. Hindu epics such as the Mahabharata and Ramayana idealize women, embodied by depictions of Draupadi, the wife of the five Pandava princes in the Mahabharata, and Sita, the wife of Prince Rama in the Ramayana. There are also many Puranic texts which elucidate the stories and symbols of solely the feminine divine. Stories and prayers from the Devi Mahatmyam and Devi Bhagavata Purana, for example, are the subject of art, poetry, dance, drama, and worship. Of course, consorts of male Gods such as Vishnu and Shiva, also figure centrally in respective Vaishnava and Shaivite scripture.

The Role of Women in Ritual

Certain rites of passage, which were traditionally for both genders, such as the sacred thread ceremony signaling the commencement of one’s religious education, over time, became the domain of boys and men only. Now there are steps, albeit small, to have such rites for both boys and girls. Regionally, there are also special rites that are just for boys and just for girls as well.

Traditionally women were not priests, but some are getting trained in officiating rituals. But a priest is not necessary to conduct all rituals. Most rituals require a married couple to perform them as a pair. There are, however, many rituals that are exclusively female, dealing primarily with the prospect of marriage and reproduction, considered two of the primary goals in life for both men and women.

The Disconnect Between Philosophy and Reality

In practice, gender equality for women in Hindu society is more challenging. Though some parts of Hindu society are matriarchal or matrilineal, many women aren’t treated as equals or accorded the dignity promised by Hindu teachings – a consequence of evolving social practices. For example, practices such as barring women from reading Vedic texts, prohibiting remarriage, or restricting property rights are not mentioned in ancient Hindu Shruti texts. On the contrary, there are many Vedic era examples of women having the liberty to do all of these things. Instead, these patriarchal practices evolved culturally due to a number of factors. Some of the most prominent included the subjugation of women as a result of urbanization and division of labor, the economic pressures placed on Hindu society as a result of invaders and wars, the spread of British colonial policies such as the prohibition of female inheritance, the reformulation of Hindu law with an emphasis on Victorian standards, and the reversal of prosperity under European mercantilism.

Reconnecting Philosophy with Reality

Long before modern, urban social justice advocacy and feminism took root in India, Hindu female saints provided a voice for the oppressed and spread messages to help other women regain many of the rights they had lost with time. With the rise of the Bhakti movement in the middle ages, the influence of women in Hinduism became even greater, as numerous female saints and poetesses composed songs and poems of devotion to God. The scores of devotionals or bhajans devoted to Krishna by the Rajput princess named Mirabai, for example, are still widely popular. Saints from underprivileged castes, such as Soyarabai, Janabai, and Nirmala wrote extensively in protest against the injustice of the Indian caste system. See the following verse by the untouchable sant Soyarabai: “O God, every human being carries impurity along with purity, why then should some human beings be treated as untouchables?” And:

“All the colours together united,

Became one colour.

Thus my Lord became

One with my song!

…

No discrimination between

The high and the low

And thus ran away farther now

The passions and anger together.

…

Now the outward sight is

Not for me,

I have gained the inward

Eye, to see Thee before me.

Says thus the poet Soyara

…”

Others like Bahinabai challenged patriarchal and priestly privilege alike. Sometimes her songs were temperate in their assertiveness:

“…A true wife is she who is aware of her own self

Being married she has to fulfil her family duties:

but she must have the craving for spiritual salvation too.

It is possible that the husband children and others may not approve.

But she must not give up her true path…”

Other times her words were fiercely critical, communicating determination to foster spiritual growth even in the context of her real suffering: “Whenever it pleases him, he beats me a lot, binds me like a bundle of sticks…My husband earned a living through practicing Veda. Where is God in this?..But my mind has taken a vow. I will not leave singing for devotion, even if I die.”

Protest songs like these helped to lay the philosophical groundwork for later colonial era reformers such as Savitribai and Jyotirao Phule, and Tarabai Shinde, who brought the fight against caste oppression and patriarchy into the arena of politics and civil institutions.

Hinduism’s embrace of bhakti (devotional worship) led to the emergence of key female spiritual reformers and saints. They have also been uplifted through the teachings and efforts of many male religious figures. The noted social reformer Swami Dayananda Saraswati, for instance, cited Vedic testimony to argue that women are entitled to Vedic study. He founded the Arya Samaj in 1875, and its members soon established colleges for teaching Hindu scriptures to girls. Swami Vivekananda, the 19th century Hindu spiritual luminary, harshly criticized the condition of women in Indian society, and staunchly advocated for their equality, education, and self-empowerment. He also proposed the establishment of a order of women, as part of the larger orders established by Adi Shankaracharya, to be managed by women only. This came to fruition in 1959.

What is the status of Women in Hinduism

What was a rarity until recently, is now becoming an increasingly common practice. Through the efforts of Lala Devraj several decades ago, for instance, women scholars were finally able to recite the Vedas and perform Vedic sacrifices publicly after several centuries. And in 1931, Upasani Baba founded the Kanyā Kumāri Sthān in Sakori (Ahmednagar district, India) where, to date, women are taught Vedas and the performance of seven sacred Vedic sacrifices every year. Influenced by this endeavor, another institution named Udyān Mangal Karyālaya was started in the city of Pune wherein women of all castes and vocations are learning to chant the Vedas and become priests. There are now thousands of Hindu women priests both within India and outside India (including the United States) and they continue to be in great demand because they are considered as sincere, learned, and pious as their male counterparts.

Today most lineages or sampradayas (“denominations”) are male-dominated in terms of leadership, but generally open to women for dedicated monastic life or other levels of involvement. There are others, however, that are lead by women such as Ammachi, Dadi Janki, Gurumayi Chidvilasananda, Karunamayi, amongst others.

Lastly in many temples, that have secular, legal governing structures, there is no differentiation between men and women made for voting or decision-making. Many temples have had women leaders – with women serving as presidents or chairmen, involved in organizing and leading religious events, and in managing temple operations.

Key Takeaways

- Hinduism has always worshipped divinity in female form as Shakti.

- Women have played prominent roles in Hindu society from ancient time till now.

- Over time, a disconnect between Hindu philosophy and reality developed, leading some women to be treated as less than equal.

- Thanks to the efforts of many reformers, women have begun to regain their ancient rights.