– By Arun Shourie

“There can be no doubt that the fall of Buddhism in India was due to the invasions of the Musalmans,” writes the author. “Islam came out as the enemy of the ‘But’. The word ‘But,’ as everybody knows, is an Arabic word and means an idol. Not many people, however, know that the derivation of the word ‘But’ is the Arabic corruption of Buddha. Thus the origin of the word indicates that in the Moslem mind idol worship had come to be identified with the Religion of the Buddha. To the Muslims, they were one and the same thing. The mission to break the idols thus became the mission to destroy Buddhism. Islam destroyed Buddhism not only in India but wherever it went. Before Islam came into being Buddhism was the religion of Bactria, Parthia, Afghanistan, Gandhar and Chinese Turkestan, as it was of the whole of Asia….”

A communal historian of the RSS-school?

But Islam struck at Hinduism also. How is it that it was able to fell Buddhism in India but not Hinduism? Hinduism had State-patronage, says the author. The Buddhists were so persecuted by the “Brahmanic rulers”, he writes, that, when Islam came, they converted to Islam: this welled the ranks of Muslims but in the same stroke drained those of Buddhism. But the far more important cause was that while the Muslim invaders butchered both — Brahmins as well as Buddhist monks — the nature of the priesthood in the case of the two religions was different — “and the difference is so great that it contains the whole reason why Brahmanism survived the attack of Islam and why Buddhism did not.”

For the Hindus, every Brahmin was a potential priest. No ordination was mandated. Neither anything else. Every household carried on rituals — oblations, recitation of particular mantras, pilgrimages, each Brahmin family made memorizing some Veda its very purpose…. By contrast, Buddhism had instituted ordination, particular training etc. for its priestly class. Thus, when the invaders massacred Brahmins, Hinduism continued. But when they massacred the Buddhist monks, the religion itself was killed.

Describing the massacres of the latter and the destruction of their vihars, universities, places of worship, the author writes,

“The Musalman invaders sacked the Buddhist Universities of Nalanda, Vikramshila, Jagaddala, Odantapuri to name only a few. They raised to the ground Buddhist monasteries with which the country was studded. The monks fled away in thousands to Nepal, Tibet and other places outside India. A very large number were killed outright by the Muslim commanders. How the Buddhist priesthood perished by the sword of the Muslim invaders has been recorded by the Muslim historians themselves. Summarizing the evidence relating to the slaughter of the Buddhist Monks perpetrated by the Musalman General in the course of his invasion of Bihar in 1197 AD, Mr. Vincent Smith says, “….Great quantities of plunder were obtained, and the slaughter of the ‘shaven headed Brahmans’, that is to say the Buddhist monks, was so thoroughly completed, that when the victor sought for someone capable of explaining the contents of the books in the libraries of the monasteries, not a living man could be found who was able to read them. ‘It was discovered,’ we are told, ‘that the whole of that fortress and city was a college, and in the Hindi tongue they call a college Bihar.’ “Such was the slaughter of the Buddhist priesthood perpetrated by the Islamic invaders. The axe was struck at the very root. For by killing the Buddhist priesthood, Islam killed Buddhism. This was the greatest disaster that befell the religion of the Buddha in India….”

The writer? B. R. Ambedkar.

But today the fashion is to ascribe the extinction of Buddhism to the persecution of Buddhists by Hindus, to the destruction of their temples by the Hindus. One point is that the Marxist historians who have been perpetrating this falsehood have not been able to produce even an iota of evidence to substantiate the concoction. In one typical instance, three inscriptions were cited. The indefatigable Sita Ram Goel looked them up. Two of the inscriptions had absolutely nothing to do with the matter. And the third told a story which had the opposite import than the one which the Marxist historian had insinuated: a Jain king had himself taken the temple from Jain priests and given it to the Shaivites because the former had failed to live up to their promise. Goel repeatedly asked the historian to point to any additional evidence or to elucidate how the latter had suppressed the import that the inscription in its entirety conveyed. He waited in vain. The revealing exchange is set out in Goel’s monograph, “Stalinist ‘Historians’ Spread the Big Lie.”

Marxists cite only two other instances of Hindus having destroyed Buddhist temples. These too it turns out yield to completely contrary explanations. Again Marxists have been asked repeatedly to explain the construction they have been circulating — to no avail. Equally important, Sita Ram Goel invited them to cite any Hindu text which orders Hindus to break the places of worship of other religions — as the Bible does, as a pile of Islamic manuals does. He has asked them to name a single person who has been honoured by the Hindus because he broke such places – the way Islamic historians and lore have glorified every Muslim ruler and invader who did so. A snooty silence has been the only response.

But I am on the other point. Once they occupied academic bodies, once they captured universities and thereby determined what will be taught, which books will be prescribed, what questions would be asked, what answers will be acceptable, these “historians” came to decide what history had actually been! As it suits their current convenience and politics to make out that Hinduism also has been intolerant, they will glide over what Ambedkar says about the catastrophic effect that Islamic invasions had on Buddhism, they will completely suppress what he said of the nature of these invasions and of Muslim rule in his Thoughts on Pakistan, but insist on reproducing his denunciations of “Brahmanism,” and his view that the Buddhist India established by the Mauryas was systematically invaded and finished by Brahmin rulers.

Thus, they suppress facts, they concoct others, they suppress what an author has said on one matter even as they insist that what he has said on another be taken as gospel truth. And when anyone attempts to point out what had in fact happened, they raise a shriek: a conspiracy to rewrite history, they shout, a plot to distort history, they scream.

But they are the ones who had distorted it in the first place — by suppressing the truth, by planting falsehoods. And these “theses” of their’s are recent concoctions. Recall the question of the disappearance of Buddhist monasteries. How did the grand-father, so to say, of present Marxist historians, D. D. Kosambhi explain that extinguishing? The original doctrine of the Buddha had degenerated into Lamaism, Kosambhi wrote. And the monasteries had “remained tied to the specialized and concentrated long-distance ‘luxury’ trade of which we read in the Periplus. This trade died out to be replaced by general and simpler local barter with settled villages. The monasteries, having fulfilled their economic as well as religious function, disappeared too.” And the people lapsed!

“The people whom they had helped lead out of savagery (though plenty of aborigines survive in the Western Ghats to this day), to whom they had given their first common script and common language, use of iron, and of the plough,” Kosambhi wrote, “had never forgotten their primeval cults.”

The standard Marxist “explanation” — the economic cause, the fulfilling of historical functions and thereafter disappearing, right to the remorse at the lapsing into “primeval cults”. But today, these “theses” won’t do. For today the need is to make people believe that Hindus too were intolerant, that Hindus also destroyed temples of others….

Or take another figure — one saturated with our history, culture, religion. He also wrote of that region — Afghanistan and beyond. The people of those areas did not destroy either Buddhism or the structures associated with it, he wrote, till one particular thing happened. What was this? He recounted,

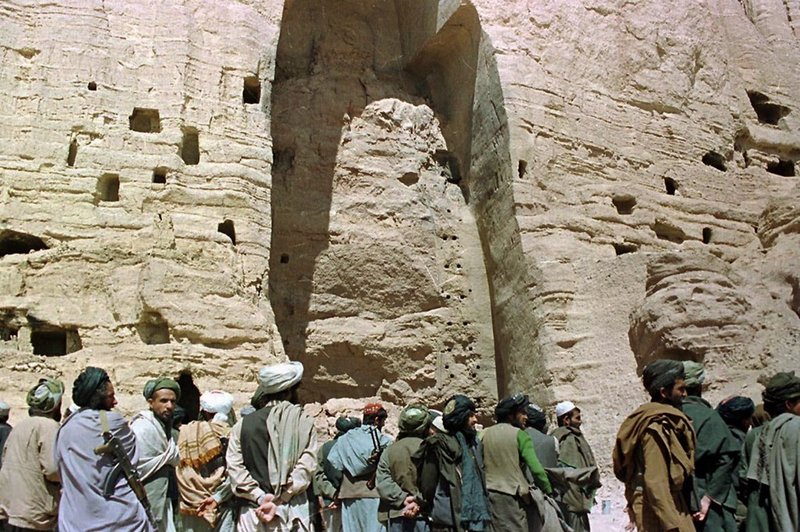

“In very ancient times this Turkish race repeatedly conquered the western provinces of India and founded extensive kingdoms. They were Buddhists, or would turn Buddhists after occupying Indian territory. In the ancient history of Kashmir there is mention of these famous Turkish emperors — Hushka, Yushka, and Kanishka. It was this Kanishka who founded the Northern School of Buddhism called Mahayana. Long after, the majority of them took to Mohammedanism and completely devastated the chief Buddhistic seats of Central Asia such as Kandhar and Kabul. Before their conversion to Mohammedanism they used to imbibe the learning and culture of the countries they conquered, and by assimilating the culture of other countries would try to propagate civilization. But ever since they became Mohammedans, they have only the instinct of war left in them; they have not got the least vestige of learning and culture; on the contrary, the countries that come under their sway gradually have their civilization extinguished. In many places of modern Afghanistan and Kandhar etc., there yet exist wonderful Stupas, monasteries, temples and gigantic statues built by their Buddhist ancestors. As a result of Turkish admixture and their conversion to Mohammedanism, those temples etc. are almost in ruins, and the present Afghans and allied races have grown so uncivilized and illiterate that, far from imitating those ancient works of architecture, they believe them to be the creation of super-natural spirits like the Jinn etc. …”.

The author? The very one the secularists tried to appropriate three-four years ago — Swami Vivekananda.

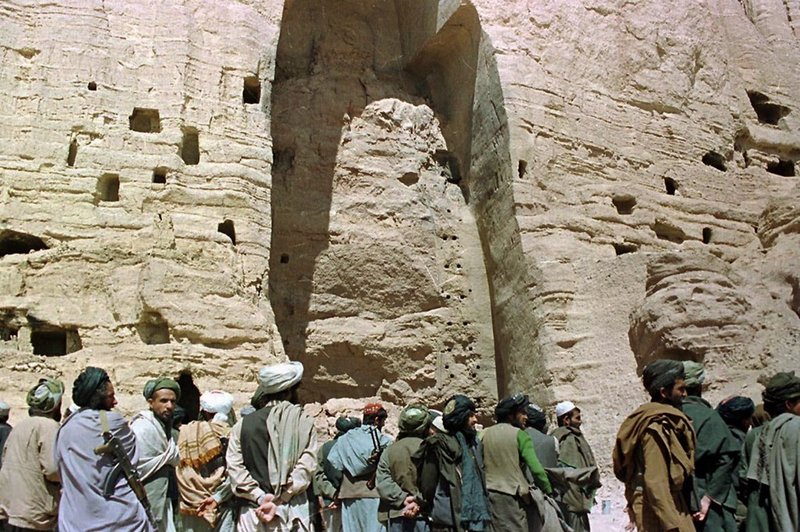

Taliban soldiers stand at the base of the mountain alcove where the world’s tallest Buddha statue once stood on March 26, 2001. The Taliban leader, Mullah Mohammed Omar, ordered the destruction of the mammoth mountain carvings and all other Buddha statues in Afghanistan. (Amir Shah/AP)

And look at the finesse of these historians. They maintain that such facts and narratives must be swept under the carpet in the interest of national integration: recalling them will offend Muslims, they say, doing so will sow rancour against Muslims in the minds of Hindus, they say. Simultaneously they insist on concocting the myth of Hindus destroying Buddhist temples. Will that concoction not distance Buddhists from Hindus? Will that narrative, specially when it does not have the slightest basis in fact, not embitter Hindus?

Swamiji focussed on another factor about which we hear little today: internal decay. The Buddha — like Gandhiji in our times — taught us first and last to alter our conduct, to realise through practice the insights he had attained. But that is the last thing the people want to do, they want soporifics: a mantra, a pilgrimage, an idol which may deliver them from the consequences of what they have done. The people walked out on the Buddha’s austere teaching for it sternly ruled out props. No external suppression etc., were needed to wean them away: people are deserting Gandhiji for the same reason today — is any violence or conspiracy at work ?

The religion became monk and monastery-centric. And these decayed as closed groups and institutions invariably do. Ambedkar himself alludes to this factor — though he puts even this aspect of the decay to the ravages of Islam. After the decimation of monks by Muslim invaders, all sorts of persons — married clergy, artisan priests — had to be roped in to take their place. Hence the inevitable result, Ambedkar writes: “It is obvious that this new Buddhist priesthood had neither dignity nor learning and were a poor match for the rival, the Brahmins whose cunning was not unequal to their learning.”

Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo and others who had reflected deeply on the course of religious evolution of our people, focussed on the condition to which Buddhist monasteries had been reduced by themselves. The people had already departed from the pristine teaching of the Buddha, Swamiji pointed out: the Buddha had taught no God, no Ruler of the Universe, but the people, being ignorant and in need of sedatives, “brought their gods, and devils, and hobgoblins out again, and a tremendous hotchpotch was made of Buddhism in India.” Buddhism itself took on these characters: and the growth that we ascribe to the marvelous personality of the Buddha and to the excellence of his teaching, Swami Vivekananda said, was due in fact “to the temples which were built, the idols that were erected, and the gorgeous ceremonials that were put before the nation.” Soon the “wonderful moral strength” of the original message was lost “and what remained of it became full of superstitions and ceremonials, a hundred times cruder than those it intended to suppress,” of practices which were “equally bad, unclean, and immoral….”

Swami Vivekananda regarded the Buddha as “the living embodiment of Vedanta”, he always spoke of the Buddha in superlatives. For that very reason, Vivekananda raged all the more at what Buddhism became: “It became a mass of corruption of which I cannot speak before this audience…;” “I have neither the time nor the inclination to describe to you the hideousness that came in the wake of Buddhism. The most hideous ceremonies, the most horrible, the most obscene books that human hands ever wrote or the human brain ever conceived, the most bestial forms that ever passed under the name of religion, have all been the creation of degraded Buddhism”….

With reform as his life’s mission, Swami Vivekananda reflected deeply on the flaws which enfeebled Buddhism, and his insights hold lessons for us to this day. Every reform movement, he said, necessarily stresses negative elements. But if it goes on stressing only the negative, it soon peters out. After the Buddha, his followers kept emphasising the negative, when the people wanted the positive that would help lift them.

“Every movement triumphs,” he wrote, “by dint of some unusual characteristic, and when it falls, that point of pride becomes its chief element of weakness.” And in the case of Buddhism, he said, it was the monastic order. This gave it an organizational impetus, but soon consequences of the opposite kind took over. Instituting the monastic order, he said, had “the evil effect of making the very robe of the monk honoured,” instead of making reverence contingent on conduct. “Then these monasteries became rich,” he recalled, “the real cause of the downfall is here… some containing a hundred thousand monks, sometimes twenty thousand monks in one building — huge, gigantic buildings….” On the one hand this fomented corruption within, it encoiled the movement in organizational problems. On the other it drained society of the best persons.

From its very inception, the monastic order had institutionalized inequality of men and women even in sanyasa, Vivekananda pointed out. “Then gradually,” he recalled, “the corruption known as Vamachara (unrestrained mixing with women in the name of religion) crept in and ruined Buddhism. Such diabolical rites are not to be met with in any modern Tantra…”

Whereas the Buddha had counseled that we shun metaphysical speculations and philosophical conundrums as these would only pull us away from practice — Buddhist monks and scholars lost themselves in arcane debates about these very questions. [Hence a truth in Kosambhi’s observation, but in the sense opposite to the one he intended: Shankara’s refutations show that Shankara knew nothing of Buddha’s original doctrine, Kosambhi asserted; Shankara was refuting the doctrines which were being put forth by the Buddhists in his time, and these had nothing to do with the original teaching of the Buddha.] The consequence was immediate: “By becoming too philosophic,” Vivekananda explained, “they lost much of their breadth of heart.”

Sri Aurobindo alludes to another factor, an inherent incompatibility. He writes of “the exclusive trenchancy of its intellectual, ethical and spiritual positions,” and of how “its trenchant affirmations and still more exclusive negations could not be made sufficiently compatible with the native flexibility, many-sided susceptibility and rich synthetic turn of the Indian religious consciousness; it was a high creed but not plastic enough to hold the heart of the people…”

We find in such factors a complete explanation for the evaporation of Buddhism. But we will find few of them in the secularist discourse today. Because their purpose is served by one “thesis” alone: Hindus crushed Buddhists, Hindus demolished their temples… In regard to matter after critical matter — the Aryan-Dravidian divide, the nature of Islamic invasions, the nature of Islamic rule, the character of the Freedom Struggle — we find this trait — suppresso veri, suggesto falsi. This is the real scandal of history-writing in the last thirty years. And it has been possible for these “eminent historians” to perpetrate it because they acquired control of institutions like the ICHR.

To undo the falsehood, you have to undo the control.