~ By Stephen Knapp, also known as Sri Nandanandana dasa, writer, author, philosopher, spiritual practitioner, lecturer and president of Vedic Friends Association (VFA)

Many people may know about Buddhism, but few seem to understand its connections with Vedic culture and how many aspects of it have origins in the Vedic philosophy. To begin with, it was several hundred years before the time of Lord Buddha that his birth was predicted in the Srimad-Bhagavatam:

“In the beginning of the age of Kali, the Supreme Personality of Godhead will appear in the province of Gaya as Lord Buddha, the son of Anjana, to bewilder those who are always envious of the devotees of the Lord.” (Bhagavatam 1.3.24)

This verse indicates that Lord Buddha was an incarnation of the Supreme who would appear in Gaya, a town in central India. But some historians may point out that Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, was actually born in Lumbini, Nepal, and that his mother was Queen Mahamaya. Therefore, this verse may be inaccurate. But actually Siddhartha became the Buddha after he attained spiritual enlightenment during his meditation under the Bo tree in Gaya. This means that his spiritual realization was his second and most important birth. Furthermore, Siddhartha’s mother, Queen Mahamaya, died several days after Siddhartha’s birth, leaving him to be raised by his grandmother, Anjana. So the prediction in the Bhagavatam is verified.

When Lord Buddha appeared, the people of India, although following the Vedas, had deviated from the primary goal of Vedic philosophy. They had become preoccupied with performing ceremonies and rituals for material enjoyment. Some of the rituals included animal sacrifices. The people had begun to sacrifice animals indiscriminately on the plea of Vedic rituals and then indulged in eating the flesh. Being misled by unworthy priests, much unnecessary animal killing was going on and the people were becoming more degraded and atheistic.

The rituals that included animal sacrifices, according to the Vedas, were not meant for eating flesh. An old animal would be placed in the sacrificial fire and, after the mantras were chanted, it would come out of the fire in a new and younger body as a test to show the potency of the Vedic mantras. However, as the power of the priests deteriorated, they could no longer chant the mantras properly and, therefore, the animals would not be brought back to life. So in the age of Kali all such sacrifices are forbidden because there are no longer any brahmanas who can chant the mantras correctly. Thus, Lord Buddha appeared and rejected the Vedic rituals and preached the philosophy of nonviolence. In the Dhammapada(129-130) Buddha says, “All beings fear death and pain, life is dear to all; therefore the wise man will not kill or cause anything to be killed.”

The Vedic literature also teaches nonviolence, but Buddha taught the people who used the Vedas for improper purposes to give them up and simply follow him. Thus, he saved the animals from being killed and saved the people from being further misled by the corrupt priests. However, he did not teach the Vedic conclusions of spiritual knowledge but taught his own philosophy.

Buddha was born in the town of Lumbini in Nepal as the son of a king of the Shakya clan. He is generally accepted to have lived during 560-477 BC but has been shown to have been born in 1887 BC and died in 1807 BC.

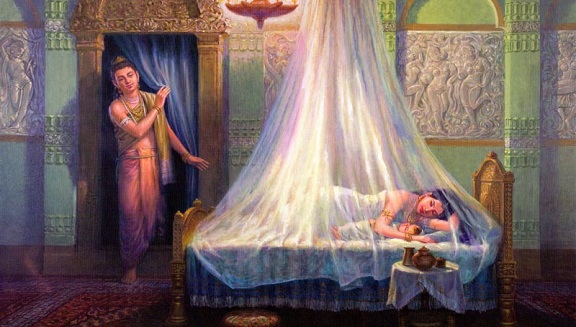

His mother, Queen Mahamaya, before she conceived him, saw him in a dream descending from heaven and entering her womb as a white elephant. After his birth his father sheltered him from the problems of the world as much as possible. Later, Buddha married and had one son. It was during this time that he began to be disturbed by the problems life forced on everyone, especially after he had seen for the first time a man afflicted with disease, another man who was decrepit with age, a dead man being carried to the cremation grounds, and a monk who had dedicated himself to the pursuit of finding a release from the problems of life.

Soon after this, at the age of 29, he renounced his family and became a wandering beggar. For six years Buddha sought enlightenment as an austere ascetic. He would eat very little food, sometimes only one grain of rice a day, and his bones would stick out as if he were a skeleton. Finally giving that up, thinking that enlightenment was not to be found in such a severe manner, he again became a beggar living on alms. When he started to eat more regularly, the five mendicants who were with him left him alone, thinking that he had given up his resolution. During this time he came to Gaya where he determinedly sat in meditation under the Bo tree for seven weeks. He was tempted by Mara, the Evil One, with many pleasures in an effort to make Gautama Buddha give up his quest. But finally he attained enlightenment. It was then that he became the enlightened Buddha.

Buddha at first hesitated to teach his realizations to others because he knew that the world would not want them. Of what use would there be in trying to teach men who were sunk in the darkness of illusion? Nonetheless, he decided to make the attempt. He then went to Benares and met the five mendicants who had deserted him near Gaya. There in the Deer Park, in present day Sarnath, he gave his first sermon, which was the beginning of Buddhism.

Buddha taught four basic truths: that suffering exists, there is a cause for suffering, suffering can be eradicated, and there is a means to end all suffering. But these four noble truths had previously been discussed in the Sankhya philosophy before Buddha’s appearance, and had later been further elaborated upon in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. So this train of thought actually was not new.

Buddha also taught that suffering is essentially caused by ignorance and our own mental confusion about the purpose life. The suffering we experience can end once we rid ourselves of this confusion through the path of personal development. Otherwise, this confusion and ignorance causes us to perform unwanted activities that become part of our karma that must be endured in this or another existence. When karma ceases, so does the need for birth and, naturally, old age, sorrow, and death. With the cessation of birth, there is the cessation of consciousness and entrance into nirvana follows. Thus, according to this, there is no soul and no personal God, but only the void, the nothingness that is the essence of everything to which we must return. Although this was the basic premise from which Buddha taught, this theory was mentioned in the Nasadiya-sukta of the Rig-veda long before Buddha ever appeared.

However, Buddha refused to discuss how the world was created or what was existence in nirvana. He simply taught that one should live in a way that would produce no more karma while enduring whatever karmic reactions destiny brought. This would free one from further rebirth.

In order to accomplish this, Buddha gave a complete system for attaining nirvana that consisted of eight steps. These were right views (recognizing the imperfect and temporary nature of the world), right resolve (putting knowledge into practice or living the life of truth and nonviolence toward all creatures, including vegetarianism), right speech (giving up lies, slander, and unnecessary talk), right conduct (nonviolence, truthfulness, celibacy, nonintoxication, and nonstealing), right livelihood (honest means of living that does not interfere with others or with social harmony), right effort (maintaining spiritual progress by remaining enthusiastic and without negative thoughts), right mindfulness (remaining free from worldly attachments by remembering the temporary nature of things), and right meditation (attaining inner peace and tranquility and, finally, indifference to the world and one’s situation, which leads to nirvana). This, for the most part, is merely another adaptation of the basic yamasand niyamas that are the rules of what to do and what not to do that are found in the Vedic system of yoga.

However, because of Buddha’s lack of interest in discussing any metaphysical topics, many interpretations of his philosophy were not only possible but were formed, especially after his disappearance. The two main divisions of Buddhism that developed were the Hinayana, or lesser vehicle, and Mahayana, or greater vehicle. The Hinayana was more strict and held onto Buddha’s original teachings and uses Pali as the language of its scriptures. It also accepts reaching nirvana as the goal of life. Hinayana stresses one’s own enlightenment and puts less emphasis on helping others, and Mahayana emphasizes the need of enlightenment for the good of others while overlooking the need to realize the truth within. The Mahayana accepts Sanskrit as the language for its texts and integrates principles from other schools of philosophy, making it more accessible to all varieties of people. Gradually, as followers came from numerous cultural backgrounds, Mahayana Buddhism drastically changed from its original form.

The ideal of the Mahayana system is the bodhisattva, the person who works for enlightenment for all other living beings. The personification of this enlightened compassion is one of the major deities of Buddhism, Avalokiteshvara, who is represented in a variety of forms and images. The mantra that is the sound representation of this enlightened compassion is om mani padme hum, which is chanted on beads by aspiring Buddhists. The vibration of this mantra evokes compassionate qualities and feelings in the heart and consciousness of a person who chants it.

A third division of Buddhism is the Vajrayana sect. This has the same principles as the Mahayana, but the Vajrayana bases its process for achieving enlightenment on the Buddhist Tantras, which are supposed to reveal a quicker path to enlightenment. The Vajrayana path is one of transforming the inner psychological energy toward enlightenment by the use of various types of yogic techniques. First they try to change their conventional perceptions of this world by identifying themselves with the Buddhist deity that they feel affinity for, and to view the mandala of the particular deity as the world.

Ultimately, this form of meditation, as well as other techniques used in this system, is meant to give one the experience of what is called the “clear light.” This clear light is said to be experienced by everyone shortly after death, but most people hardly notice it because they are not prepared for it. The idea is that if one is prepared for it before death, it can help one to be ready to merge into it when he sees it after death.

As Buddhism flourished, the Hinayana spread through the south in Ceylan, Burma, and Thailand, while the Mahayana spread to the North and East and is now found primarily in Tibet, China, and Japan. The Mahayana school still uses knowledge of kundalini and the chakras in its teachings, other topics that are traced to the Vedic system. It is this Mahayana school which has now developed more than twenty sects with a variety of teachings that, in some cases, especially in the West, have become so distorted that it is impossible to distinguish the original principles that were established by Buddha.

Besides the Vedic similarities in Buddhism already mentioned, there are many additional correlations between the Vedic literature and the Buddhist religion of the Far East. For example, the word Ch’an of the Ch’an school of Chinese Buddhism is Chinese for the Sanskrit word dhyana, which means meditation, as does the word zen in Japanese. Furthermore, the deity Amitayus is the origin of all other Lokesvara forms of Buddha and is considered the original spiritual master, just as Balarama (the expansion of Lord Krishna) in the Vedic literature is the source of all the Vishnu incarnations and is the original spiritual teacher. Also, the trinity doctrine of Mahayana Buddhism explains the three realms of manifestations of Buddha, which are the dharmakaya realm of Amitabha (the original two-armed form is Amitayus), the sambhogakaya realm of the spiritual manifestation (in which the undescended form of Lokesvara or Amitayus reigns), and the rupakaya realm, the material manifestation (which is where the Buddha in the form of Lokesvara incarnates in so many other different forms). This is a derivative of the Vedic philosophy. Thus, Lokesvara is actually a representation of Vishnu to the Mahayana Buddhists.

Furthermore, all the different incarnations of Vishnu appear as different forms of Lokesvara in Buddhism. For example, Makendanatha Lokesvara is the same as the Vedic Matsya, Badravaraha Lokesvara is Varaha, Hayagriva in Buddhism is the horse-necked one as similarly described in the Vedic literature, and so on. And the different forms of Lakshmi, Vishnu’s spouse as the Goddess of Fortune, appear as the different forms of Tara in the forms of White Tara, the Green Tara, etc. Even the fearful forms of Lokesvara are simply the fearful aspects of Lord Vishnu, as in the case of the threatening image of Yamantaka, who is simply the form of the Lord as death personified. The name is simply taken from Yamaraja, the Vedic lord of death.

Many times you will also see Buddhist paintings depicting a threefold bending form of Bodhisattvas and Lokesvaras much the same way Krishna is depicted. This is because the Bodhisattvas were originally styled after paintings from India, which were prints of Krishna. Most images of Tara are also similar to paintings of Lakshmi in that one hand is held in benediction. And Vajrayogini, the Buddha in female aspect, is certainly styled after goddess Kali or Durga. Kuvera, the lord of wealth in the Vedic culture, is Kuvera Vaishravana in Buddhism. There are many other carry-overs from the Vedic tradition into Buddhism that can be recognized, such as the use of ghee lamps and kusha grass, and the offerings of barley and ghee in rituals that resemble Vedic ceremonies. In this way, we can see the many similarities and connections in Buddhism with Vedic culture, which is the origin of many of the concepts found within Buddhism.

Therefore, after the disappearance of Lord Buddha, the authority of the Vedas and Vedic culture was reinstated by such scholarly personalities as Shankaracarya, Ramanujacarya, Madhvacarya, Nimbarka, Baladeva Vidyabushana, Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, and others.

Thus making humor the `midwife of truth’, Zen masters converted Buddha’s laughter into the medium of enlightenment. But laughter was also an expression of enlightenment, Buddha’s laughter is a state of release from inner tensions into inner harmony. The Buddha does not laugh at himself or at others, he does not laugh because he has acquired something others don’t have. The laughter is neither cynical, sarcastic, bitter nor defiant. It is the laughter of compassion, an amusement at the interplay of knowledge and ignorance that makes up the joys and sorrows of what we call life.

Thus making humor the `midwife of truth’, Zen masters converted Buddha’s laughter into the medium of enlightenment. But laughter was also an expression of enlightenment, Buddha’s laughter is a state of release from inner tensions into inner harmony. The Buddha does not laugh at himself or at others, he does not laugh because he has acquired something others don’t have. The laughter is neither cynical, sarcastic, bitter nor defiant. It is the laughter of compassion, an amusement at the interplay of knowledge and ignorance that makes up the joys and sorrows of what we call life.